Why Oregon’s Ski Industry Is in Big Trouble

Background

When it comes to skiing and riding in the United States, the state of Oregon has long been a strong regional choice for those in the Pacific Northwest. That’s why recent events in the state have been so alarming, with a business environment that has quietly become the most hostile in the country for ski resort operations. And due to developments in the state in recent weeks, there is a real possibility that every major ski resort in the state could soon be legally barred from opening.

So what’s exactly happened, and how likely is the so-called “nuclear” scenario to actually happen? Well, in this piece, we’ll go through the series of events that made Oregon uniquely susceptible to the crisis it currently faces, whether any other states have faced similar issues, and how the state could feasibly dig itself out of the hole it now finds itself in—despite the fact that it currently may not have the political will to do so. Let’s jump into one of the least known impending catastrophes in the American ski industry.

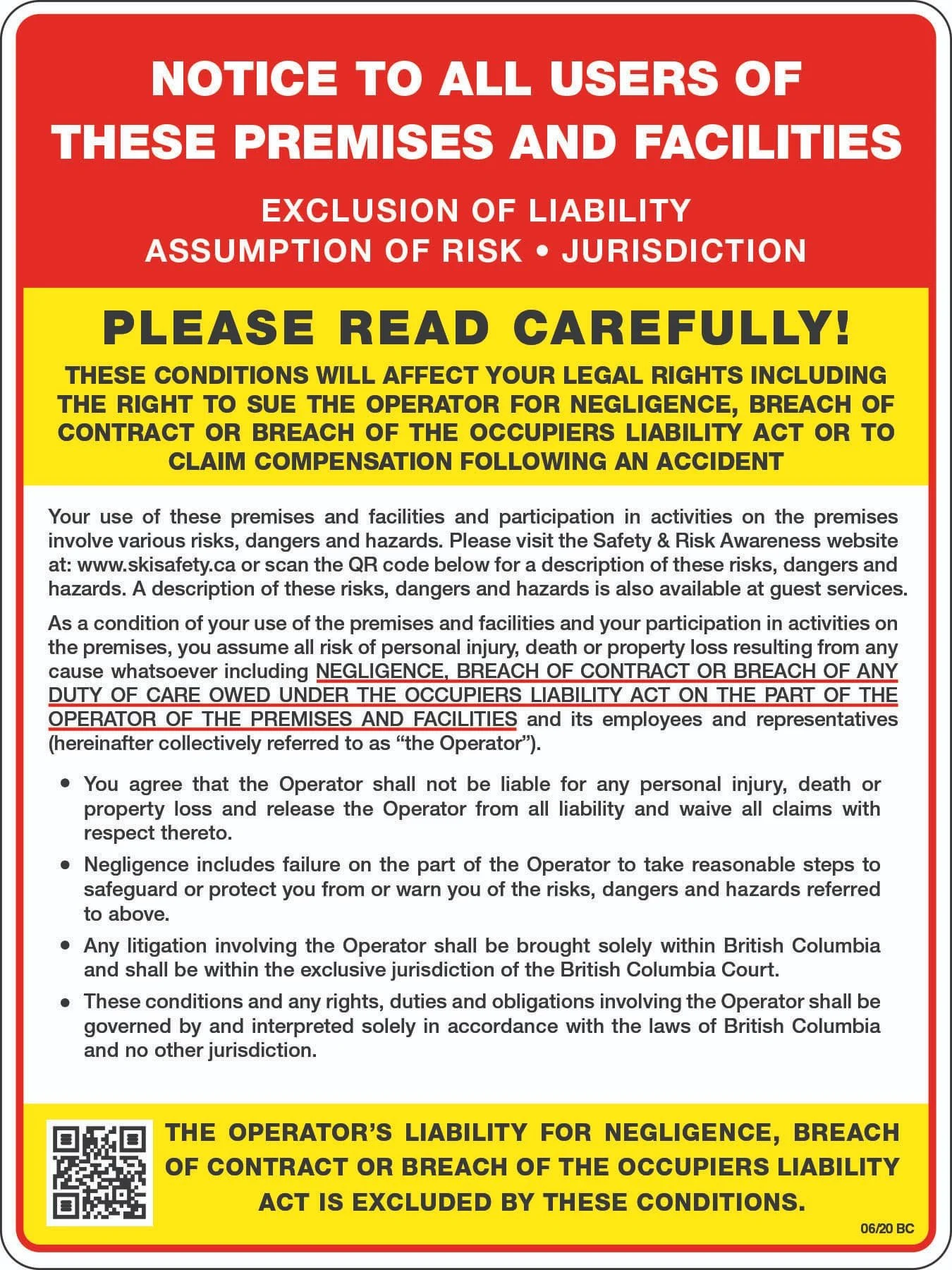

Liability waivers like this one have long protected ski resorts from catastrophic lawsuits stemming from high-risk activities.

Oregon’s Outdoor Liability Insurance Background

The crisis that Oregon currently faces primarily boils down to one factor: liability insurance. For many decades, ski resort liability insurance worked generally the same in Oregon as it did in other states. Liability waivers have long served as the legal backbone of the outdoor recreation industry, allowing ski resorts and adventure operators to function in high-risk environments without the constant threat of catastrophic lawsuits. In most Western states, these waivers are enforceable so long as they’re clear and voluntary, shielding operators from claims arising from "ordinary negligence"—think catching an edge, hitting a tree, or colliding with another skier or rider. This legal clarity gives insurers confidence, enables resorts to keep their premiums in check, and arguably helps keep lift ticket rates at practical levels too.

But in Oregon about a decade ago, a series of legal events completely upended all of that.

Bagley v. Mt. Bachelor: The Case that Shook the Foundations

In 2006, 18-year-old Myles Bagley was snowboarding at Central Oregon’s Mount Bachelor when he hit a jump in the resort’s terrain park. Unfortunately, the landing went horribly wrong. Bagley suffered a severe spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the waist down. He later argued the jump was defectively designed and unsafe.

Like most snowboarders and skiers, Bagley had signed a liability waiver when he purchased his season pass. The agreement released Mount Bachelor from responsibility for injuries, even those resulting from negligence. Despite this, Bagley filed a lawsuit, claiming the resort had acted recklessly in building the terrain feature.

What followed was a years-long legal battle that culminated in a landmark 2014 Oregon Supreme Court decision: Bagley v. Mt. Bachelor.

In a ruling that reverberated across the outdoor recreation industry, the court declared Mount Bachelor’s liability waiver unenforceable. The court determined the contract was both unconscionable and against public policy, effectively invalidating essentially every liability waiver used in the state at the time.

The justices emphasized three main points in their decision: (1) the waiver was a contract of adhesion—non-negotiable and imposed by a party with disproportionate power; (2) skiers and riders had no ability to modify the terms, and thus no meaningful choice, and (3) perhaps most critically, the waiver attempted to release the resort from liability even for its own negligent conduct. The court found these circumstances contrary to Oregon’s legal principles, arguing it disincentivized safety and violated the public interest.

On paper, the ruling was intended to preserve legal recourse for seriously injured parties. But unfortunately, it eventually became clear that the decision, while presumably well intentioned, had taken things a little bit too far.

As of 2022, Oregon is the only Western state that does not enforce outdoor recreation liability waivers.

2014-2025: Lawsuits, Rate Spikes & Retreating Insurers

Over the next decade, Oregon’s ski industry entered a treacherous state. With liability waivers rendered largely unenforceable by the Bagley ruling, insurance companies began viewing the state as toxic territory. This came as injured patrons at ski resorts—and even summer recreation users—started suing more effectively, with damage demands climbing into the tens of millions.

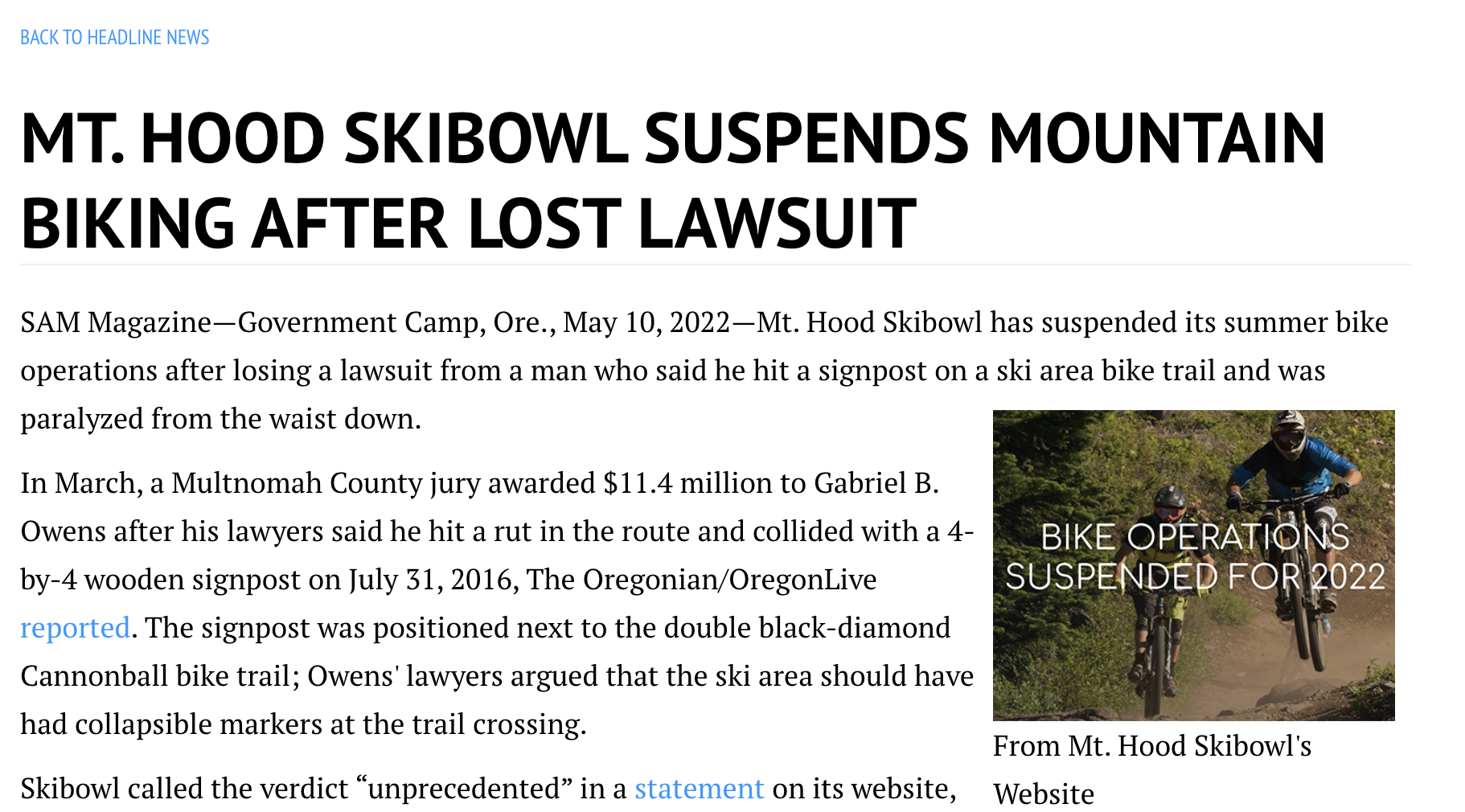

The first major post-Bagley case took shape in 2016, when a mountain biker at Mount Hood Skibowl was paralyzed after hitting a drainage rut and colliding with an unpadded wooden post along a downhill trail. Although the incident occurred during the summer, not the winter season, the case had major implications for the liability environment surrounding outdoor recreation in Oregon. In 2022, a jury awarded the rider over $11 million in damages, ruling that Skibowl had failed to take reasonable safety precautions despite signage and waiver protections. It was one of the largest single verdicts against a recreation operator in Oregon history, and in response, Skibowl completely shut down their bike park operations and hasn’t restarted them since.

Mount Hood Skibowl was forced to suspend its bike park operations in 2022 following an eight-figure lawsuit, and the mountain hasn’t restarted them since. Source: SAM Magazine

The legal risk wasn’t limited to Skibowl. Mount Bachelor also became a focal point for legal scrutiny, with two $15 million wrongful death suits following a pair of 2018 tree well fatalities, and a nearly $50 million claim filed after a child’s 2021 death after sliding into rocks on an icy run. Even community-oriented areas like Mount Ashland—despite facing no public lawsuits—reported being overwhelmed by rising insurance costs. The resort’s general manager noted a 129% increase in liability premiums over 12 years, with another 30% spike expected in 2025.

But it wasn’t just increasing premiums that occurred. By early 2025, brokers reported that fewer and fewer firms were willing to even consider underwriting ski resorts in Oregon. Outdoor recreation companies formed coalitions like Protect Oregon Recreation to plead for legal reform, warning that without enforceable waivers or other liability shields, the state's entire outdoor recreation industry—not just ski resorts, but also including bike parks, rock gyms, and river rafting companies among others—was at risk. The insurance market was drying up, and fast.

Specifically when it comes to ski resorts, one potential indicator of these legal and financial pressures is how unpredictable Oregon’s terrain openings have become. Despite reasonably strong snowfall most seasons, resorts like Mount Bachelor and Mount Hood Meadows are consistently among the least resilient in terms of terrain access—and in a recent analysis, we ranked Oregon dead last for reliability among major ski regions. There's no doubt that weather plays a major role here—Oregon’s maritime precipitation and volcanic geography can complicate slope cover and safe operations—but many in the industry believe the state’s legal environment only makes things worse. Resorts may be incentivized to act overly cautiously given the threat of excruciating lawsuits, keeping trails closed longer than necessary out of fear that a misstep could result in litigation. Anecdotally, the Summit Express lift at Mount Bachelor, which directly served the terrain where the 2021 death took place, was closed continuously for a period of approximately a month later that same season; it’s possible that conditions justified this closure, but this was an especially long suspension, even for this fickle terrain zone, and it’s easy to see the resort opting to err on the side of legal caution given the circumstances.

Mount Bachelor’s Summit lift, pictured above, operated significantly less reliably after a fatal accident that occurred on its terrain.

The Breaking Point: Safehold’s Exit and the Last Insurer Standing

So if it’s been over a decade since the Bagley ruling, why are we bringing all of this up now? In June 2025, the Oregon insurance situation went from precarious to existential. Safehold Special Risk, a major ski industry insurer that covered resorts like Mount Hood Meadows, Timberline Lodge, and Cooper Spur, announced it was pulling out of Oregon entirely. In doing so, it said Oregon had become unworkable: although the state accounted for only a fraction of its clients, it produced half of its $1M–$10M payouts.

That exit left Oregon with just one viable ski resort insurer: MountainGuard. MountainGuard, a legacy provider with national reach, has continued to serve the state—but not without concern. Its leadership made clear that a single massive verdict could force them to reassess. Should MountainGuard exit as well, no insurer may be willing to step in. And because without insurance, resorts can’t legally operate, this move would completely and immediately shut down every Oregon ski resort.

Legislative Attempts to Fix the Isssue

So given this pending catastrophe, has Oregon’s government made any efforts to address it? Well, at least claiming to recognize the growing crisis, Oregon’s state legislature has proposed several bills over the last decade, all aiming to restore partial legal protection for outdoor recreation operators.

In 2025, the most promising was Senate Bill 1196, which would have allowed liability waivers to cover ordinary negligence—but not gross or reckless misconduct. A similar House bill, HB 3140, had the same aim. Supporters said this was a common-sense compromise already in place in most other Western states. It would have brought Oregon in line with its neighbors while still allowing injured parties to sue in cases of gross negligence or willful misconduct.

The bills initially gained momentum. SB 1196 advanced through the Senate Finance and Revenue Committee, and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle signaled they would support the bill if it came to a vote. In fact, multiple state legislators and even Governor Tina Kotek indicated they would sign the bill into law if it passed the House and Senate.

But despite committee approval and apparent legislative support, neither SB 1196 nor HB 3140 were brought to a floor vote before the end of the 2025 session. Trial lawyer groups lobbied heavily against the reform, arguing it would strip injured parties of their right to sue and reduce incentives for resorts to maintain safe conditions. And in the end, legislative leadership declined to advance the bills to the floor, effectively killing them.

The failure was a huge disappointment for resort operators and insurance carriers alike. It marked the third time in ten years that similar legislation had failed in Oregon. And with this specific defeat, the state’s recreation industry moved to the precarious point at which it finds itself today. Indeed, Safehold had explicitly warned lawmakers it would exit the state if these reforms didn’t pass. When the bills died, Safehold made good on that promise—pulling out of Oregon and sending a clear message that the state would pay a steep price for its inaction.

If the last major insurer pulls out of Oregon, nearly all recreational activities will be forced to shut down immediately—and a solution may take awhile to materialize.

The Catastrophe: What Happens If the Insurance Disappears?

If Oregon’s last major ski insurer, MountainGuard, pulls out of the state, the effects would be both immediate and far-reaching.

Ski resorts that operate on Forest Service land, like Mount Bachelor, Mount Hood Meadows, and Timberline Lodge, are legally required to carry general liability insurance to maintain their permits. Without it, they’d be forced to shut down operations overnight. And that sudden stop wouldn’t just hit the slopes. Entire communities would feel the aftershocks.

Towns like Government Camp, Ashland, and Bend depend on consistent winter and summer visitation to support their tourism economies. Hotels, restaurants, gear shops, ski schools, and shuttle services would all be thrown into crisis. The liability issue stretches beyond skiing, too—rock gyms, rafting companies, zipline tours, mountain bike parks, and even climbing guides all rely on similar liability protections and insurance to stay afloat. If Oregon can’t find a fix, the state’s entire outdoor recreation economy could begin to unravel.

Central Oregon would be hit hardest. Over the past two decades, Bend has evolved from a modest town into a booming four-season destination, with outdoor recreation as the cornerstone of its growth. Its population has more than doubled since 2000, and a significant portion of its winter economy revolves around Mount Bachelor, Oregon’s biggest ski resort by a significant margin. While according to locals we interviewed, the resort struggled under mismanagement during what they called POWDR Corp’s “dark ages” in the mid-to-late 2000s, things turned around after POWDR infamously lost Park City and shifted its attention back to Bachelor, significantly boosting investment and bringing about a rebound in winter visitation.

A forced shutdown—triggered not by mismanagement but by insurance collapse—could send Bend into another economic slump. And since Bachelor operates a popular summer bike park, the fallout wouldn’t be limited to just ski season. Bend sees nearly twice as many visitors in summer as in winter, and the ripple effects of a shutdown would be felt year-round.

But if MountainGuard does leave, would the shutdown be permanent? Well, despite the catastrophic consequences in the interim, probably not.

A complete collapse of Oregon’s ski industry would force the state’s hand. While lawmakers have failed to pass legal reform in previous sessions, a full-scale closure would almost certainly bring enormous political pressure to act. We’d almost certainly see a fast-tracked bill to reauthorize liability waivers for ordinary negligence (something like SB 1196), and likely additional action through an emergency legislative session to get the industry back on its feet.

Still, a fix wouldn’t restore operations overnight. Insurers that have already fled the state may not return immediately, especially if legal uncertainty lingers. The state might have to lean on short-term solutions like government-backed risk pools or cooperative insurance programs. And even if those stopgaps work, rebuilding trust with national insurers could take years.

So while Oregon’s ski resorts might not be shuttered forever, the disruption would be deeply damaging—and the recovery could be long and uneven—for businesses and communities alike.

The nearby state of Idaho faced similar liability issues a few years ago, but government entities took initiative to correct course.

How Oregon Could Dig Itself Out: The Idaho Precedent

So has any other state ever faced something like this? Oregon’s path forward might seem uncertain, but it’s not without precedent. In fact, just next door in Idaho, the ski industry faced a similarly dire moment—and ultimately managed to stabilize the situation before it spiraled out of control.

The crisis in Idaho began in 2023, when the state’s Supreme Court allowed a wrongful death lawsuit against Sun Valley to proceed, despite the state’s long-standing Ski Area Liability Act. The case involved a skier who crashed into a snowmaking tower and suffered fatal injuries, and the court’s initial ruling opened the door to potential jury trials for incidents that had traditionally been considered part of the inherent risk of skiing. The decision sparked panic among resort operators, who feared a flood of litigation and a potential loss of insurance coverage. Bogus Basin even began adding extra signage around equipment purely as a legal precaution.

But in a rare about-face, the Idaho Supreme Court reversed course in mid-2025. The justices determined that because the hazard was clearly marked and padded, the skier had assumed the risk—meaning the resort was not liable under Idaho’s statute. The decision reinstated critical liability protections, and lawmakers are now working to clarify and strengthen the law further in the next legislative session. Just a few years earlier, Idaho also passed legislation upholding waiver enforceability for outfitters and guides, signaling a broader commitment to protecting the outdoor recreation economy.

The lesson for Oregon? Even when the legal foundation starts to crack, a coordinated response from courts and lawmakers can restore balance. While Oregon’s situation is further along than Idaho’s was—and arguably more severe too—there’s still a window for action.

Oregon’s ski resorts are facing several multi-million-dollar lawsuits that could come to a head within the coming months. Even one payout could move the last state insurer to pull the plug. Source: KATU

How Much Time Does Oregon Have to Act?

So just how long is this window for action we just mentioned? Well, based on the current legal landscape and timeline of active cases, the threat is probably not quite as immediate as the next few months. However, the lack of urgency with which the Oregon legislature seems to be handling this means they could be setting themselves up for a historic fumble.

The “Ticking Time Bomb” Lawsuits

So realistically-speaking, what could actually happen that would cause MountainGuard to leave—and consequently trigger a statewide resort shutdown? Well, the company did cite that a single major verdict could cause it to leave the state, and a few major cases making their way through the legal system could very well be the “nuclear verdict” that would force the company’s hand. Take, for example, the most high-profile active case: a $6.2 million lawsuit filed in early 2025 by a ski coach who was struck by a snowmobile at Mount Hood Meadows. While the case is likely months away from settlement or trial, it is significant—and could result in a large payout. In addition, the wrongful-death lawsuit against Mount Bachelor, which seeks nearly $50 million in damages, is still winding through the legal process after being filed in August 2022. There could be other non-public cases or other factors that could cause MountainGuard to leave in the coming months too; for example, the Mount Hood Skibowl case that forced the mountain to shut down its bike park wasn’t even reported on until the eight-figure verdict came down.

The Oregon Government’s Leisurely Timeline

So how should we look at these cases now? Well, for the state of Oregon, there’s some good news and some bad news. The good news is that while these cases remain a looming threat, they’re unlikely to reach a verdict or settlement before this fall’s insurance renewal period. Most Oregon ski resorts operate on annual insurance cycles that renew in September or October, so unless something unexpected like an accelerated settlement or surprise verdict happens, it’s likely that MountainGuard will remain in the Oregon market for at least one more winter.

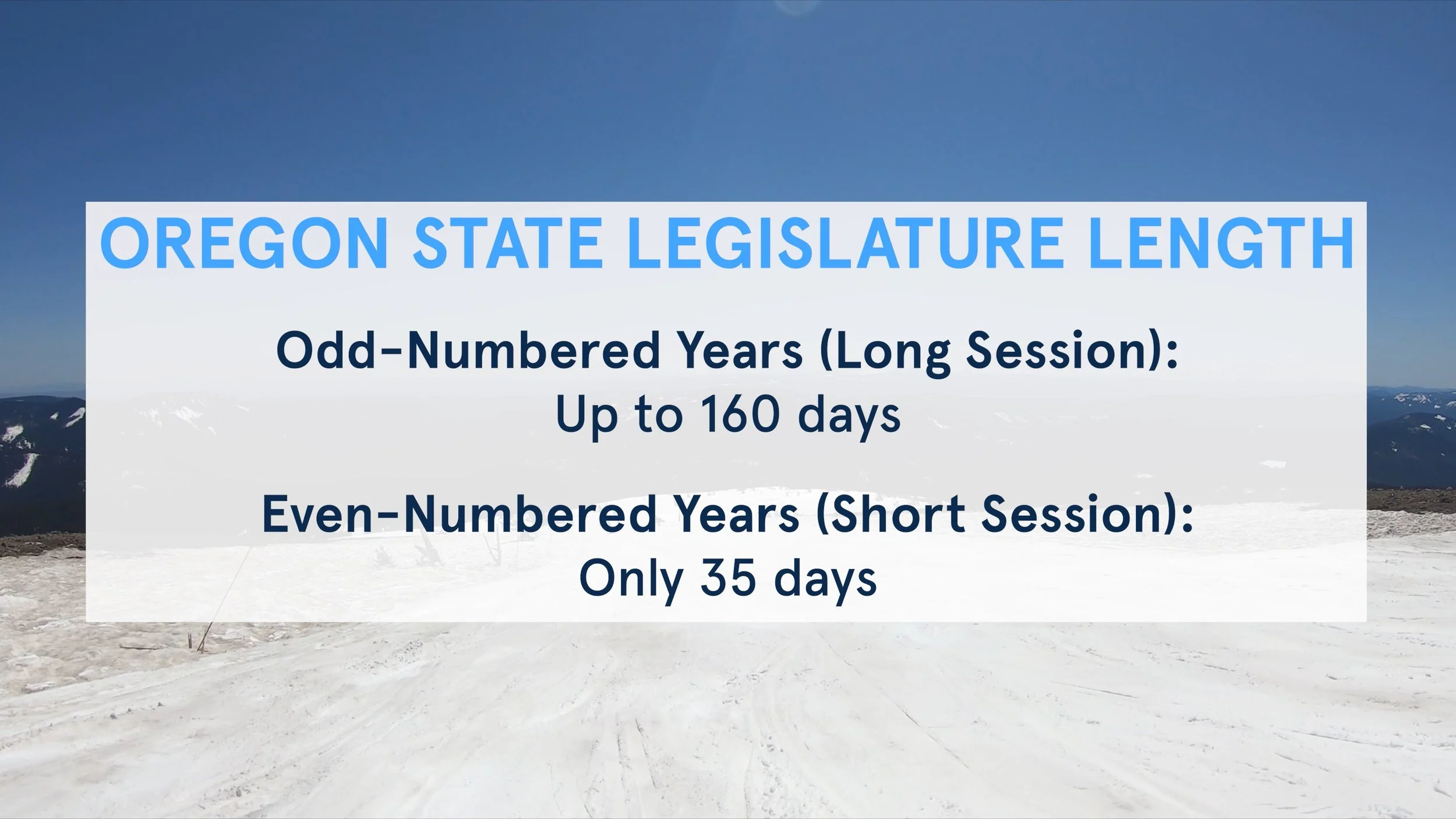

But here’s the bad news: the threat hasn’t gone away, and the major lawsuits currently in motion could very well result in eight-figure payouts over the next 12 to 18 months, which could force MountainGuard to exit before the 2026-27 season. But perhaps the most concerning part of this whole situation is there’s very little chance the state will act in time to prevent that outcome. Oregon’s next legislative session won’t be until February 2026, which is already over six months from now at this point. But in even years, the state’s legislative session is just 35 days long, practically only allowing for priorities like budgets, transportation, housing, and public safety—and making it exceedingly unlikely that liability reform would even be considered for debate. It is worth caveating that in recent days, an emergency session was called for this upcoming August; however, it's narrowly focused on transportation funding and transit layoffs, so the chances of liability insurance being taken up are essentially slim to none. So unless another emergency session is called or a surprise court ruling comes about, the legal environment is unlikely to improve before February 2027—and by that point, there’s a concerningly real chance it will be too late.

The Oregon legislature’s comically short session length in even years means that it won’t realistically be able to tackle the liability crisis again until 2027—unless it calls an emergency session.

Final Thoughts

The collapse of Oregon’s ski resort liability protections was set in motion by a tragic injury and what one could reasonably assume was a well-meaning court ruling. But a decade later, the lack of a legislative fix threatens the survival of the state’s entire ski industry.

Ultimately, the sky isn’t falling quite right now, and it’s more likely than not Oregon’s ski industry will have one more season of insurance left. However, if no action is taken soon, the window to avoid a full-scale coverage collapse in the coming months could close fast. For now, all eyes are on the legislature, the courts, and the lone insurer left.

So with all of this being said, is there any way you can take action? Well the biggest way is if you live in Oregon, contact your state legislators and tell them how you feel. If you don’t live in Oregon, consider supporting organizations like Protect Oregon Recreation, which are actively lobbying for legal reform in this space and could use all the help they can get. And finally, no matter where you live, tell your friends and family about this—the more people who put pressure on the key players here, the more likely lawmakers are to prioritize solutions before there isn’t a ski season anymore.