Vail Resorts’ $21 Million Court Loss Explained (And Why You Should Care)

Resorts like Mount Hood Meadows are at risk of a complete shutdown within the next 12-18 months due to an escalating liability crisis.

Background

When it comes to the last 12 months, developments for Vail Resorts have not been decidedly what one might call good. But within the past few weeks, the news has arguably gotten even worse. Earlier this month, the company was hit with a multi-million dollar jury verdict after a serious accident at one of its ski areas. But while the verdict on its own certainly doesn’t look good for Vail Resorts, the decision also has far bigger implications for several other high-profile incidents Vail is already facing—plus creates new precedent for the American ski industry as a whole.

So what exactly forced Vail Resorts to pay out such a large amount of money, and what does it all mean for the U.S. ski industry going forward? Well, in this piece, we’ll go through the background of this case, its decisioning and reasoning, and what all of this means for you as you go on your next ski trip.

The Paradise lift at Crested Butte, pictured above, was the site of the catastrophic accident that spawned all of the legal developments discussed in this piece.

A Catastrophic Ski Lift Accident in Crested Butte

Before we jump into the decision that cost Vail Resorts tens of millions of dollars, we have to provide some background to it. In March 2022, a 16-year-old skier named Annie Miller was visiting Colorado’s Crested Butte ski resort with her church youth group. On what would become her final run of the trip, she and her father attempted to load the resort’s Paradise Express quad chairlift, a high-speed detachable quad installed in 1994 that’s similar to lifts found at many other destination ski resorts in the country. Detachable lifts are notable for their slower terminal speeds, which typically allows for easier loading and unloading and gives lift attendants more time to spot misload problems.

However, something went wrong during this particular loading process. Annie never settled fully into the chair before it left the terminal and began accelerating to full speed, reportedly leaving her dangling in mid-air as the chair kept moving. Her father shouted for the operator to stop the lift and clung desperately to her arm, but by the time the liftie reacted and actually stopped the lift, it was too late. Unfortunately, Annie slipped from the chair, falling roughly 30 feet onto hard-packed snow. The impact shattered her C-7 vertebra and left her paralyzed from the chest down.

In the aftermath, Miller faced a long rehab process and the life-changing reality of becoming a paraplegic. Given the circumstances, her family believed the lift crew had been negligent in failing to stop the chair when it was obvious she hadn’t loaded safely. That belief set the stage for the years-long legal battle that ultimately culminated in the landmark ruling earlier this year.

The Initial Lawsuit and Liability Waiver Implications

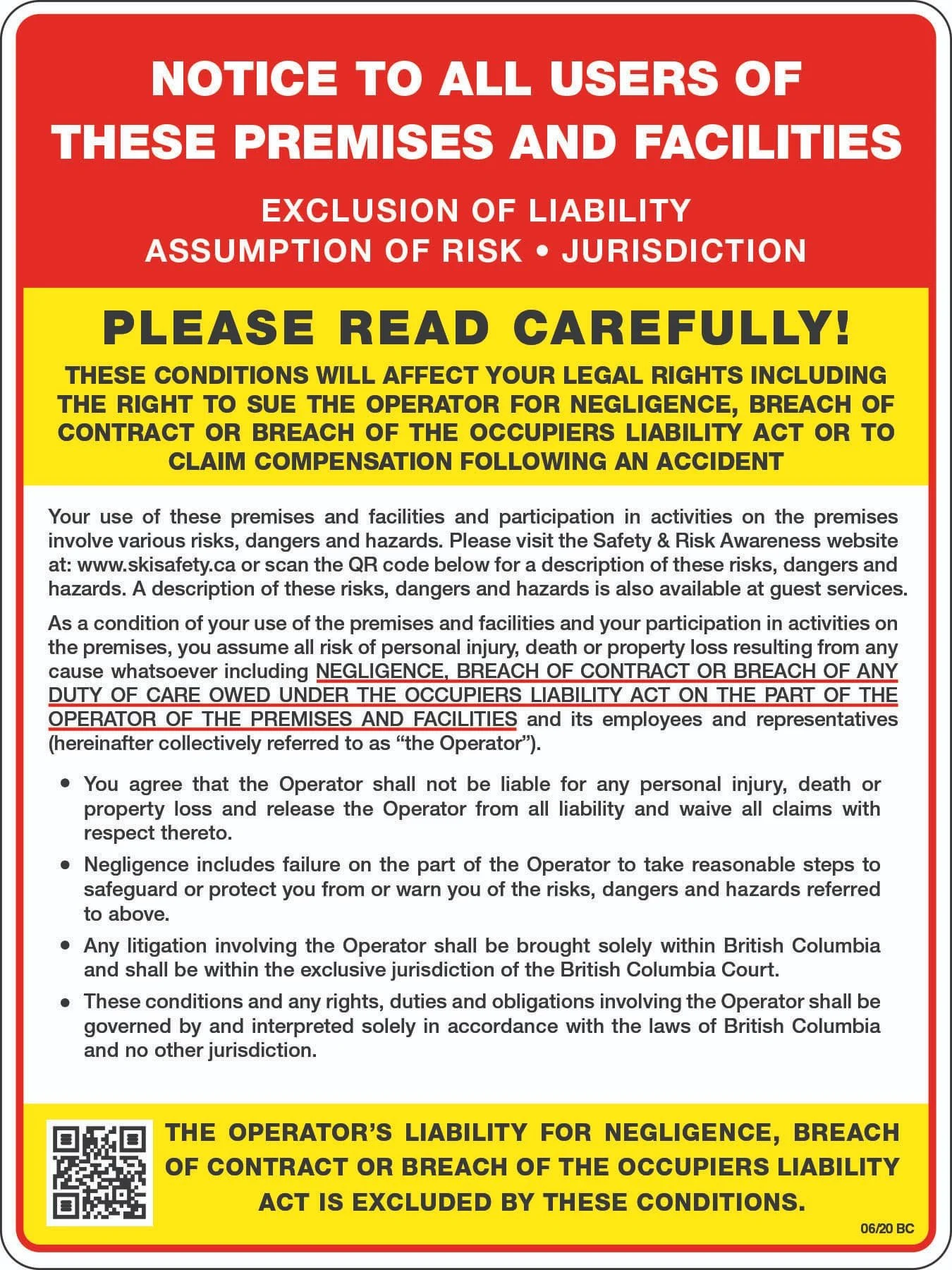

Liability waivers like this one have long protected ski resorts from catastrophic lawsuits stemming from high-risk activities.

After the accident, Miller’s family filed a lawsuit against Crested Butte and its parent company, Vail Resorts, in Broomfield County District Court (the jurisdiction where Vail’s headquarters are located). The suit alleged multiple claims: that the resort had breached its duty of care to safely operate the lift, that the lift operators were negligent in failing to respond appropriately, and gross negligence for recklessly disregarding safety. Now, under a situation like this, there are two major defense strategies that a ski resort company like Vail Resorts might rely on: 1. the Colorado Ski Safety Act, and 2. the standard liability waiver included with every lift ticket in the state.

Under the Colorado Ski Safety Act, skiers and riders accept many inherent risks of in-bounds skiing—including weather, snow conditions, or the potential for collisions—and ski areas enjoy broad protections from lawsuits over those inherent risks. Notably, however, the law explicitly excludes chairlift accidents from the definition of inherent skiing risks, so that shield wasn’t going to do them much good in this case. On the other hand, the liability waiver provided Vail Resorts with much more solid ground. Like most ski areas, Crested Butte required guests to sign a liability release when purchasing a ticket or pass product. Vail’s lawyers argued that this waiver—a click-through agreement Miller’s father had signed when buying their passes—should bar any claim of negligence relating to the lift fall. For decades, such waivers have given ski resorts near-blanket immunity from lawsuits; one can debate the ethics of it, but it’s long been a rule of thumb in the industry that by signing a ticket or season pass waiver, guests give up their right to sue for ordinary negligence on the mountain.

And initially, Vail Resorts’s liability waiver argument actually held up. In April 2023, a Broomfield County judge agreed in large part with Vail Resorts and dismissed the bulk of the Miller family’s claims, including the ordinary negligence and “duty of care” allegations, leaving only the gross negligence claim intact. In other words, the court ruled that because Miller’s ticket waiver warned of risks like misloading or falling from a lift, the resort was contractually protected against standard negligence claims stemming from the incident. Miller’s case was not unique in this regard—for years, many ski injury lawsuits have been halted in their tracks by similar waivers and state statutes shielding resorts from liability for skiing accidents.

However, the Millers did not give up. They appealed the dismissal to the Colorado Supreme Court, arguing that a ski resort cannot contract away its legal duty to operate chairlifts safely under state law. They argued that even if a skier or rider signs a waiver, the resort should still be accountable if it violated specific safety statutes or regulations designed to protect the public. This set the stage for a high-profile decision at Colorado’s highest court that ultimately led to the multi-million-dollar payout a few weeks ago.

The Miller v. Crested Butte case loosened immunity protections for ski resorts in the case of negligence.

Miller v. Crested Butte: A New Negligence Standard

In May 2024, the Colorado Supreme Court issued a landmark 5-2 decision that set a new precedent for ski area immunity in the state. The court drew a crucial distinction between ordinary negligence and negligence per se—the latter meaning negligence based on violating a law or regulation designed for safety. The justices ruled that while general risks outlined in the waiver (like falls from lifts due to misloading) could still be waived by a contract, a ski resort could not use a waiver to shield itself from liability if it failed to obey safety laws or regulations. This was the first time Colorado’s highest court had ever ruled against the blanket enforceability of ski liability waivers, marking a turning point in the state’s winter sports industry where a new type of liability lawsuit against a ski area was allowed to move forward in the state.

Perhaps the main law at issue in this decision was the Ski Safety Act, with a specific focus on its provisions on lifts. Notably, the Ski Safety Act itself contains language that “no ski area operator is immune from lift-related injuries”, reinforcing that lift safety is a non-negotiable duty. The Supreme Court essentially said that ski areas cannot sidestep those duties with a waiver, because the legislature intended for resorts to be held accountable if they don’t follow the rules. Two justices dissented on this part, arguing that a signed waiver should block all negligence claims, even those involving statutory violations, but they were ultimately outvoted.

For the outdoor recreation industry both in Colorado and other states, this ruling did not go unnoticed. Liability waivers are ubiquitous not just at ski resorts but virtually any recreation business. A coalition of youth camps and outdoor outfitters had even filed briefs supporting Vail Resorts, warning that undermining waivers could make insurance unaffordable and force changes that limit outdoor access for kids. On the flip side, advocates for injured guests celebrated the decision as a long-overdue check on an industry that had grown too complacent behind its liability shields.

In late August, Vail Resorts was handed down a $21 million court loss. For a variety of reasons, only $12 million of this amount was actually payable. Source: Denver7

The Jury Verdict: $21 Million (And a Reality Check)

But that Supreme Court decision wasn’t the end of the Miller case. After the waiver circumstances were decided on, the Miller case proceeded to trial in summer 2025 on the remaining negligence claims. After a two-week trial featuring nine days of testimony, a six-member jury in Broomfield County returned a verdict in late August 2025. They found that the lift operators had indeed violated industry safety standards—essentially confirming that the resort failed to meet the legal duty of care required under state regulations. But notably, the jury stopped short of deeming the conduct gross negligence (reckless or willful disregard for safety), instead classifying it as ordinary negligence. This nuance mattered because if the Supreme Court hadn’t ruled the way they did, the gross negligence charge would have been the only one allowed to proceed to trial, and the family would have in all likelihood lost the case entirely.

The jurors awarded Miller a total of $21.1 million in damages for her catastrophic injuries—a sum that included roughly $5.3 million for noneconomic losses (pain, suffering, loss of enjoyment of life), another $5.3 million for physical impairment, and $10.55 million for future economic losses such as medical care and lost earnings.

This all being said, Colorado law did impose a dose of reality on the $21 million award. State statutes cap noneconomic damages in ski cases at $690,000, far below what the jury granted for pain and suffering. Additionally, the jury assigned 25% of the fault to the Miller family—essentially concluding that by signing the waiver (and perhaps by Annie’s initial trouble loading the lift), the family bore some responsibility. We’re not going to dissect the logic of how the jury arrived at that percentage, but as a result, Miller’s recoverable compensation came out to $12.4 million. While far less than $21 million, this is still a historic sum in a ski lift injury case. It’s believed to be the first and only jury verdict against a ski resort based on failing to meet lift safety standards, marking a crack in the long-standing armor of liability waivers.

Despite public disagreement with the decision, Vail Resorts announced it would not appeal and agreed to pay the $12.4 million, bringing the case to a close.

Industry Aftermath

So what does this all mean for the American ski industry, both in Colorado and beyond? Well, the first thing to get out of the way is this ruling does not mean that other states are headed for a crisis like the one that’s been occurring in Oregon over the past several years, and one that we covered in depth in a piece a few months ago. In Oregon specifically, state courts invalidated liability waivers entirely, making for a much more extreme liability situation for ski resorts operating there. In Colorado, waivers still apply to ordinary negligence, meaning that ski resorts are not on the hook for every incident that happens on premise, provided they follow all applicable laws. And given circumstances that are pretty much unique to Oregon, we’d expect any rulings in other states to be fairly similar to the one in Colorado as well.

In the wake of this legal development, skiers and riders may see resorts become more strict with operator training or lift operations on stormy days.

What This Means for the Skiing Public

Despite the legal drama, the fundamental ski experience isn’t expected to change dramatically for consumers—at least not immediately. A spokesperson for the NSAA, when asked if the Miller case would alter day-to-day operations, said that given the foundational importance of chairlifts, the “guest experience is unlikely to change significantly.”

Where skiers and riders might notice subtle changes is in how resorts manage risk on the margins. Ski areas could become more strict with operator training regiments or running lifts on days with inclement weather, perhaps choosing to err on the side of caution where in the past they might have previously pushed the envelope to keep guests happy. You might see more signage, announcements, and staff reminders about lift safety on your next ski trip, especially at Vail-owned resorts that will want to show that they are proactively encouraging safe ridership in the wake of all the PR here.

Perhaps the biggest change, especially if you are in Colorado, is to your legal rights. As a skier or rider, you’ve probably clicked past those liability waivers dozens of times without much thought. After Miller’s case, you should understand that those waivers are not absolute for the resorts anymore. If, in the unlikely event you or a companion are hurt due to a resort truly failing to adhere to safety rules, there may be legal recourse despite the paperwork you signed. That said, this doesn’t mean every injury at a ski area is suddenly a ticket to a lawsuit payday. The Colorado ruling was narrow: it allows claims when safety laws are broken, but it upheld waivers for ordinary mishaps and “inherent risks” of skiing or riding. So if you simply catch an edge and wipe out, or even if you misload a lift and the operator does everything right yet you fall, the waiver will likely still stop any claim you might make.

For the millions of skiers and riders likely to hit the slopes in the U.S. this winter, this case probably brings up a number of other questions. The first natural concern might be whether riding a chairlift at a resort like this is still safe. The reassuring news is that chairlift accidents like the one that injured Annie Miller remain exceedingly rare, and skiing overall is statistically very safe when it comes to lift transportation. It’s important to note the odds of being seriously injured on a ski lift are about 1 in 73 million rides—those are long odds, to say the least. Modern lifts are built and inspected to high standards, and serious malfunctions (like detachments or rollbacks) are uncommon. You’re far more likely to get injured from a bad fall on a ski run than from anything involving a lift.

The other area of concern for consumers might be cost and access. With such a big change to liability precedent, one might assume that insurance costs will go up, even if the circumstances aren’t as extreme as those in Oregon. And if insurance costs do rise for resorts, some of that expense may trickle down to ticket prices or season pass costs. But in our view, an insurance-driven price increase is unlikely, given the fact that incidents that aren’t directly a ski resort’s fault are still covered by liability waivers. However, we’ll have to wait and see if any insurers decide to pull out of Colorado in the coming years to know for sure.

Despite the array of headline-grabbing lift accidents, it’s important to note that these types of serious injuries are extremely rare (about 1 in 73 million).

Should Vail Resorts Be Worried?

But where this ruling could have the biggest impact is in what it means for Vail Resorts’ bottom line over the coming years. Now let’s be clear, from a financial standpoint, a large company like Vail Resorts is not in existential danger from one verdict. Vail reported over $290 million in net profit in the most recent 12-month period, and a $12 million payout, while unwelcome, is recoverable for a corporation of that size. The bigger worry is that this is far from the only case related to lift negligence that Vail is currently grappling with, and in fact, the other ones that it is facing might be even more high profile and might be even more clearly their fault.

In December 2024, a chair on Heavenly’s Comet Express slid backward into another chair, injuring several riders and prompting a federal and state investigation. Then, in February 2025, a chair on the Flying Bear lift at Attitash actually detached from the cable and fell roughly twenty feet, sending a passenger to the hospital. Final investigation reports haven’t been released, but the early facts in both cases point toward mechanical or maintenance failures that, if confirmed, would almost certainly qualify as violations of tramway-safety regulations. That is exactly the kind of statutory breach that voids the protection of a standard liability waiver under the new Colorado precedent—and it would give plaintiffs a far clearer path to significant jury awards. While as far as we’re aware, plaintiffs in both of those cases were not as severely injured as Annie Miller was, the fact that there were several more people affected across those two cases does play a significant role in how much a potential jury award could be.

Vail Resorts faced two high-profile chairlift accidents in Heavenly (pictured) and Attitash last winter. It is quite possible the Crested Butte decision will be used as precedent for another multi-million dollar case.

Source: xamfed | Reddit

This comes at a time when Vail’s revenue growth has flattened and management has been focused on cost-cutting. Even though the company remains profitable, a string of verdicts in the $10-20 million range would begin to matter, especially if insurers respond by hiking premiums or pushing higher deductibles. The amounts Vail pays to settle or litigate lawsuits aren’t broken out as a public line item, but for a company that has spent years squeezing expenses—and had this circumstance come to head last year when Park City ski patrollers went on strike over a wage raise that probably would’ve amounted to a couple million dollars cumulatively at most—having to redirect tens of millions toward legal judgments is probably not what they want.

Despite all these less-than-ideal circumstances, Vail’s valuation could still hold up for a couple of reasons. The company recently reinstated longtime leader Rob Katz as CEO after parting ways with Kirsten Lynch, who was at the helm when all three lift incidents occurred. Public-company valuations hinge as much on investor confidence as on hard numbers, so if Katz convincingly pivots the company toward aggressive lift maintenance and visibly safer operations—showing that accidents like these won’t happen again—market perception could improve and the stock could benefit. But the reverse is also true: if Vail continues to experience high-profile lift accidents, investor sentiment could sour. The Crested Butte case itself took roughly three years to wind through the courts, and any future Heavenly or Attitash lawsuits are likely to follow a similar multi-year timeline. Over that period, all eyes will be on Vail to prove that it truly has its safety house in order.

It’s also worth noting that Vail Resorts is far from the only lift operator that is likely going to face cases like this based off of the new precedent. In just the past three years, the following American ski resorts have had lift malfunctions that have resulted in injuries to patrons: Big Sky, Montana Snowbowl, Red Lodge, and Willamette Pass. The latter of these resorts is in Oregon, so it’s likely to face that much harsher liability environment specific to that state that we covered earlier, but the former three are in Montana, and while it’s important to note that the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling is only binding in Colorado, we wouldn’t be surprised to see that state’s courts adopt a similar legal framework to Colorado’s. We might see new lawsuits or the revival of old ones in other states testing the waters. It’s unclear which of these incidents were caused by negligence on the operators part, if any, but don’t be surprised if some of these cases reach high-profile resolutions in the not so distant future.

Vail Resorts won’t collapse from this verdict, but it’s clear that the next few years could spell trouble—especially with two additional incidents that could potentially work its way through the legal system.

Final Thoughts

So no, Vail Resorts isn’t going to collapse from this multi-million dollar verdict. But the next two years for Vail Resorts could be pivotal. Colorado’s Supreme Court has set new precedent for how negligence per se is treated at ski resorts, and with Vail still facing at least two additional incidents that could presumably involve negligence from an operational perspective, the way these are handled could significantly impact the future of Vail Resorts, plus the American ski industry as a whole.

When it comes to the impact for skiers and riders, the decision in this case delivers a clear and important message: ski resorts are not above the law when it comes to basic safety. For decades, the balance of power was tilted such that injured guests had virtually no chance in court, even if a resort blatantly failed to adhere to safety rules. Now, at least in one state, that balance has been adjusted. Ski areas remain shielded from frivolous claims—you still can’t sue just because you hit a tree or took a tumble off a cliff—but they can no longer hide entirely behind the fine print of liability waivers if they themselves create dangerous conditions by violating safety requirements.

What do you think about this development? Anything that you’re worried about in terms of the implications? Let us know in the comments below.