Why Europe’s Top Ski Resorts Are Cheaper Than America’s Mediocre Ones

Enormous European resorts with luxury amenities and weeks’ worth of terrain to explore often cost under €100 per day, while an average American resort less than a tenth the size can charge over $200 for lift tickets.

Picture This:

You’re standing in Les 3 Vallées—the largest ski area on the planet. Over 340 official runs, 160+ high-speed lifts, dozens of villages, and seemingly unlimited terrain no matter your ability. And the price to ski all of it? 82 euros. About 96 U.S. dollars.

Now jump to upstate New York. Windham Mountain. A pretty acceptable regional hill—four detachable lifts, a dozen or so groomers, and usually ice by 11 a.m. The size? Maybe one-ninetieth of Les 3 Vallées. But the price? Up to $225 for a single-day lift ticket.

Now, sure—this is an extreme comparison. One is the crown jewel of European skiing, and the other is an out-of-touch American resort trying to masquerade as a private club. But even when you look outside this anecdote, when you compare destination resorts, Europe consistently offers way fancier lifts and bigger footprints than the U.S.—and still charges a lot less per day.

So how is it that the world’s biggest and most advanced ski destinations cost a fraction as much as America’s mid-tier resorts? Is it corporate greed? Labor rules? Cost of living? Well, the real answer goes way deeper. Let’s dive right into it.

Even before the 20th century, fully functional mountain towns were well-settled in the European Alps in countries like Switzerland and Austria.

Source: Monovisions

Two Totally Different Histories

To understand why European and American ski markets have such vast discrepancies with infrastructure and pricing, we have to start with how the industries on each respective continent were born. This is way too complicated to go into full detail in this one piece, but in a nutshell, skiing plugged into places that already existed in Europe, whereas in the states, it generally didn’t.

Long before skiing became a sport, towns in the Alps were already built around farming, trade routes, and railways. When ski lifts were introduced, they were added to places that already had roads, power, permanent residents, schools, and local governments rather than empty wilderness. In many of these places, a gondola isn’t just for skiers and riders on vacation—it’s a part of daily life and local transportation, used year-round by residents, workers, and commercial visitors.

In the United States, the order reversed. Modern destination skiing was often built on high federal land far from cities, accessible by a single canyon road or a state highway that a private company had to make viable. The resort had to build almost everything from scratch—base lodges, parking lots, water systems for snowmaking and sewage, and employee housing, among other things, had to be built independently. Over time, many of these places turned into full-on towns because the ski resort existed, not the other way around. There were a couple of former mining towns that turned into ski resorts in the United States, but ski lifts in these towns were almost universally built after the mining industry died, often decades later, with the goal of restarting collapsed economies rather than supporting ones that still existed.

It’s also worth noting the importance of ski towns in Europe after World War II. After the war, rural Alpine regions across Austria, France, Switzerland, and Italy were in crisis. Farm incomes were falling, young people were leaving mountain villages for cities, and entire communities were at risk of depopulation. Local governments saw tourism—and especially skiing—as a way to reverse that decline. So they began treating ski infrastructure the same way they treated bridges, trains, or utilities: as public goods essential to keeping mountain regions alive.

Because ski lifts in Europe are still a part of everyday life in many mountain towns, they’re often treated like public infrastructure, even today. The entities behind them are not always private corporations pursuing a narrow return; they can be municipal companies, mixed public-private ventures, or firms backed by cantonal development banks, regional governments, and tourism boards. The logic is straightforward: if a lift sustains jobs, tax receipts, and year-round vitality in a mountain valley, funding it is akin to funding a road or a tramline. That support takes many forms. There are outright capital grants for lift replacements, snowmaking reservoirs, and slope stabilization projects. There are low-interest loans and guarantees that drop financing costs for big pieces of hardware. There are bed taxes—the two or three euros per person on your hotel bill—earmarked for tourism infrastructure and marketing that directly or indirectly strengthen the resort’s balance sheet. There are national and EU-level programs meant to keep rural regions competitive; a detachable gondola or tram that connects villages and keeps young people employed qualifies as a public good in that worldview.

The government doesn’t build every piece of the lift network, but these circumstances do mean the resort company isn’t carrying the full cost. As a result, European ski resorts can charge less per day without compromising on a state-of-the-art lift network.

European mountain towns often have ski lifts directly integrated into the town as an important aspect of local transit.

In the United States, cases of public funding for skiing are few and far between. Most major resorts operate under special-use permits on U.S. Forest Service land. The land is public; the lifts, lodges, snowmaking systems, and patrol buildings are private. Operators pay a fee based on revenue, undergo rigorous environmental review for expansions and replacements, and then raise and spend the money themselves. The government regulates, but it does not write checks for high-speed chairs. That has two consequences. First, almost every major capital item—lift replacements, snowmaking expansions, water storage, employee housing, parking improvements—must be financed out of the resort’s own earnings or private capital. Second, the regulatory timeline is long and uncertain. NEPA review, scoping, alternatives analysis, wildlife studies, seasonal construction windows, and potential appeals lengthen paybacks and raise the effective discount rate on any project.

The math is just harder. If you are a U.S. operator, you recover that math through every channel you control: season passes, day tickets, lessons, rentals, food, lodging, summer attractions, and real estate. Unlike a European lift firm that can count on a canton’s guarantee or a municipal co-investment, you are essentially a stand-alone utility inside private land or a federal forest.

Lift Manufacturers in Europe

Ski resorts in the Alps tend to have much more dramatic terrain than those in North America, requiring European ski lifts to feature more advanced infrastructure.

Another reason European resorts tend to have more advanced lift systems is less due to subsidies, and more because the companies that design and build the world’s most sophisticated chairlifts, gondolas, funitels, tramways, and 3S lifts were founded in the Alps and still operate there today. Doppelmayr (Austria), Garaventa (Switzerland), Leitner (Italy), and Poma (France) all started in Europe in the late 19th or early 20th centuries because that’s where skiing as a mass tourism industry first exploded, and that’s where the mountain topography demanded the innovation.

Unlike most North American ski areas—which, as we mentioned, were built after World War II on gentler, forested mountains—Alps resorts were built in steep, rugged valleys with huge vertical drops, sharp ridgelines, and towns located thousands of meters below the ski terrain. Moving people efficiently through that kind of topography required specialty aerial ropeways with long unsupported spans that simply weren’t needed in America—so the engineering culture developed there first.

These companies refined and scaled their technology by building lift after lift in the Alps, innovating aerial tramways, gondolas, and eventually detachable chairlifts, and by the time skiing took off in North America in the 1960s, European firms were already the global leaders. So perhaps unsurprisingly, the bigger, more spread-out, and jagged footprints of the European Alps also contributed to its lift industry being better.

Today, the European Alps market still represents the biggest concentration of high-capacity, high-complexity lifts in the world, so the newest technology—eight-seater chairlifts, heated-seat bubbles, funitels, tri-cable gondolas, and even underground funiculars—almost always appears in Europe first. Manufacturers can install, test, and iterate more quickly because their factories are nearby, local regulations are familiar, and resorts upgrade more often.

American ski areas still buy lifts from these same manufacturers—through their U.S. subsidiaries like Leitner-Poma or Doppelmayr USA—but permitting costs, lower skier volumes, higher legal exposure, and less government involvement make it harder to justify multi-hundred-million-dollar projects. In a nutshell, that’s why Europe has things like the 3S Matterhorn Glacier Ride network, the Vanoise Express, and the St. Anton Galzig “Ferris wheel” gondola, while major U.S. resorts still even consider high-speed six-packs to be cutting-edge.

The Vanoise Express at France’s Paradiski has the highest capacity of any double-decker cable car in the world, fitting 200 people per cabin.

The Definition of “Resort”

Okay, so it’s now clear that Europe has some built-in advantages in terms of resort size and lift infrastructure. But what exactly is that definition of “resort”? Well, when understanding how expensive skiing in the U.S. is, it’s important to note that operating an American ski area is generally more complex, both legally and operationally, than in much of Europe. American resorts tend to promise something European ones do not: boundary-to-boundary skiing. This means everything within the resort boundary, including glades, cliffs, and chutes, will be patrolled, avalanche mitigated, marked, roped off if necessary, and kept reasonably safe. As one might expect, this takes quite a bit of manpower to achieve effectively.

On the other hand, in Europe, only the marked pistes are actively part of the ski resort. Most terrain outside of those pistes, even if it is just off the side of a trail, is not officially the resort's responsibility—and as a result, it won’t be managed unless it’s absolutely necessary to protect the piste network or resort infrastructure. Given this circumstance, it’s extremely rare for slopes with significant hazards to be included as in-bounds resort terrain that’s included with your lift ticket, even though some rather extreme off-piste can be accessed directly by these lifts. It's also worth noting that in much of Europe, rescue and accident coverage isn't included with a standard lift ticket, although the cost to add that insurance is usually pretty small, only coming in at a few Euros a day.

Another costly circumstance for American resorts is greater legal exposure compared to their European counterparts. For a variety of reasons beyond this article’s scope, U.S. ski areas see higher lawsuit rates, larger and less predictable potential damage awards, and broader documentation and discovery requirements when defending claims. Taken together, these factors result in more money spent on operations, insurance programs, and legal defense at ski resorts in the United States.

When skiing or riding off the marked trails at European resorts, there is no guarantee that the terrain is patrolled or mitigated, even within resort boundaries.

The U.S. Duopoly

If the story ended there, you might already expect U.S. tickets to be more expensive just from the structural circumstances—and you could probably understand why the lift infrastructure is a step behind as well. But there’s a second engine behind today’s extraordinary lift ticket rates, and it is entirely strategic on the part of a few powerful players in the industry. Within the past few years, you may have heard of two major ski resort companies in the United States: Vail Resorts and Alterra Mountain Company. And that’s for good reason, because over the past decade, Vail and Alterra have completely rewired American skiing with the Epic and Ikon passes.

These passes seemed like fantastic deals when they were first announced, giving skiers and riders weeklong or season-long access to dozens of world-class resorts for only around $1,000. But these seemingly incredible deals for frequent skiers and riders served a secondary purpose; they were designed to make resorts less dependent on good weather. Under a last-minute lift ticket model, weather could not be relied on for visitation; if there were a snow drought or, heaven forbid, rain, people simply wouldn't show up for their vacations. So these companies flipped the model. Instead of earning money when people arrived, they wanted to earn money before winter even started.

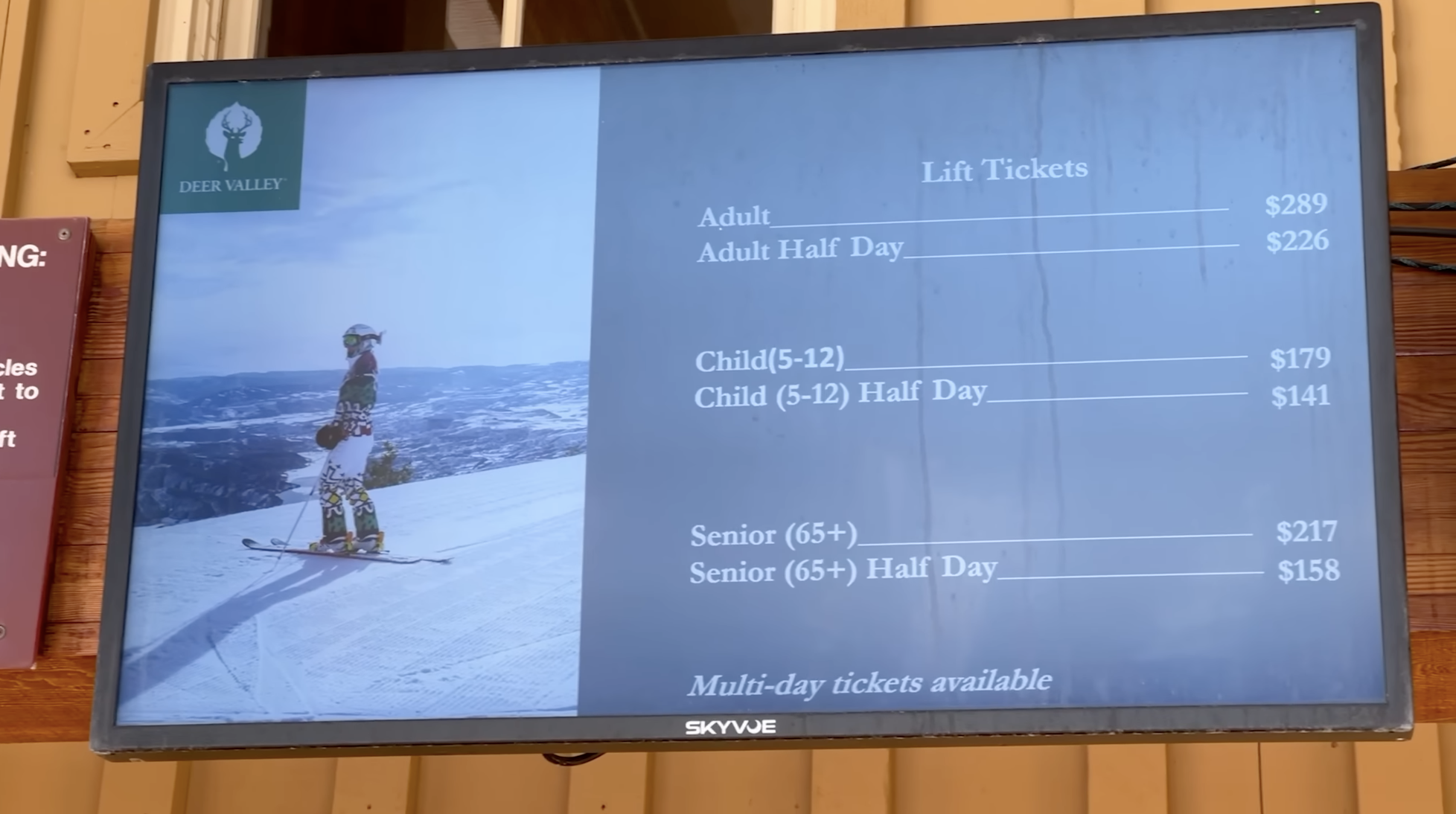

To push people in that direction, they not only made buying a season or multi-day pass feel like a good deal, but the only reasonable option. And to make that work, they also made day tickets extremely expensive. At nearly every destination ski resort in the United States, single-day walk-up tickets now cost $150 or more. And if you go on a weekend or holiday, it's the exception rather than the norm if you find tickets that cost less than $200 for a single day. And almost nauseatingly, at places like Deer Valley, Breckenridge, and Steamboat, single-day walk-up tickets now cost around $300 or more—and at the most expensive ski resorts in the country, Vail and Beaver Creek, a 1-day holiday walk-up ticket goes for a simply unconscionable $356 this year.

Many major ski resorts in the US are now charging near or in excess of $300 for a single day of access.

But there’s an important nuance here: the Epic and Ikon Pass suites are no longer exclusive to the unlimited or multi-resort season access passes that are either over or close to four figures. As of 2025, another important part of their strategy is the existence of their day-pass equivalents: the Epic Day Pass and Ikon Session Pass. These are essentially discounted bundles of 1-7 days of skiing that you buy before the season begins. If you purchase them in early fall—usually before early December—you can ski places like Vail, Park City, Snowbird, or Big Sky for discounted rates.

The Epic Day Pass is quite flexible and provides access to world-class mountains like Vail, Breckenridge, and Whistler for as low as $128 for a 1-day pass, and upper-tier mountains like Keystone, Heavenly, and Stowe for 1-day rates starting at $103. The Ikon Session Pass isn’t quite as strong of a deal; it only comes in two-, three-, and four-day versions, still ends up costing close to $150 per day even at its best value, and has essentially universal holiday blackouts. But while that's still more than major European resorts, it's nowhere near the $200-$300 walk-up window rates—and the strategy of rewarding early-season purchasers is still abundantly clear.

Powder Mountain in Utah now charges around $200 for daily lift tickets without being part of a multi-resort pass, pricing many customers out of the resort entirely.

But early-season discounts don’t exist everywhere in the United States. Some independent resorts that aren’t part of Epic or Ikon—like Powder Mountain in Utah and Windham in New York—have raised their day ticket prices into the $200 range without offering any sort of early-season discounted multi-resort pass. It's probably fair to say these resorts looked at the regular lift ticket market, saw that Vail and Alterra normalized $200+ day tickets, and followed suit—even though they don’t offer the subscription-style early commitment model of those bigger corporations.

Yes, Powder Mountain and Windham both sell season passes, and rates can be more reasonable on off-peak weekdays, but for anyone with a typical work schedule visiting for only a day or two, there’s no realistic way to avoid paying an absurd rate at either of them. The result is that skiing or riding at these mountains is now effectively limited to people with substantial disposable income or locals who can afford to buy full season passes.

Okay, but absent those few resorts we just discussed, it’s not completely accurate to say that the U.S. offers absolutely no way to get on the slopes for a reasonable value. In addition, for those who don’t care about a destination-level experience, there are still several smaller, independently-run hills that offer affordable rates. But for the most part at destination resorts, this value only exists for people who are willing and able to prepay months ahead of time—and one could argue the discounts for shorter trips are only worth it at Vail-owned resorts and a handful of Ikon-affiliated mountains with pre-season products that are cheaper than the Session Pass. In Europe, you can wake up, decide to ski or ride, and still get a reasonable day rate. In the U.S., that kind of spontaneity has disappeared at most destination-level resorts, and even some regional ones.

Will This Reality Change?

So another question becomes: is this going to change? Are American resorts ever going to be as nice as Europe’s in the lift department? Will those same American resorts ever be as affordable as Europe again? On the other hand, are European ski resorts going to see the same outrageous lift ticket price creep as in the states?

Let’s tackle the lifts first, and unfortunately, public funding for resort infrastructure isn’t politically realistic in the U.S. in most circumstances. There have been a few edge cases; the most notable might be the Telluride Village Gondola network, while up in Canada, the Whistler Peak 2 Peak tricable gondola was built as part of a fully-enclosed lift network between Whistler and Blackcomb for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games. And in Utah, many folks have heard of a proposed and rather controversial transit gondola in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

But generally in North America, aerial lifts are seen as a way to access a luxury recreation sport rather than a means of transportation. Liability laws and insurance environments aren’t changing anytime soon, and if anything, they’ve gotten even more unfavorable in certain U.S. states like Oregon.

The Mountain Village Gondola in Telluride, CO is a rare example of a publicly funded, free-to-use ski lift at a ski resort in the United States.

When it comes to some relief for American lift ticket prices, closing that gap seems a little bit more feasible, but still unlikely in the near term. Epic and Ikon’s entire business model depends on front-loading revenue before the season starts. They want you to pay several months in advance, and day tickets are intentionally overpriced to push you into that system.

But in recent weeks, it seems that both Vail Resorts and Alterra have realized some of the pitfalls of their strategies, and both companies have introduced significantly discounted “friends and family” tickets that folks who know someone with a pass can use to get a walk-up window ticket for up to 50% off. Depending on the resort, these discounts can bring an American lift ticket down to something much closer to European pricing, although their use comes with important fine print on availability and, in some cases, the presence of the lending passholder.

At this point, it does not seem like Europe is likely to fall victim to the same subscription-model pricing issues as America, and a big reason is that no single company or set of companies control enough of the market to make it work. And we know this not hypothetically, but because Vail Resorts actually owns two ski resorts in Switzerland—Andermatt and Crans-Montana.

Vail’s European resorts, such as Switzerland’s Andermatt, match European pricing models for lift tickets as opposed to the company’s pricing strategy used at its North American resorts.

But even though Vail charges well over $200 for a walk-up lift ticket at places like Vail or Park City in the U.S., their Swiss resorts still top out at around 99 Swiss francs for a same-day ticket on weekends or holidays. It’s not necessarily that Vail Resorts wouldn’t like to raise last-minute lift ticket rates at their Swiss resorts, it’s that if they tried, the market simply wouldn’t tolerate it. In other words, they’d lose customers to the dozens of other European destinations that still offer reasonable prices and similar terrain.

But that doesn’t mean that Europeans aren’t afraid of the prospect of big American corporations taking over their ski hills. In fact, in late October 2025, citizens in the Swiss municipalities of Laax, Falera, and Flims voted to take public ownership of their resort infrastructure, and they’ve done this explicitly after Vail Resorts expressed interest in taking over the mountains in the region. Now that the municipalities are on track to take over the resorts, it will be effectively impossible for Vail or any American company to swoop in.

Does This Tell The Whole Story On Cost?

Another important question to ask is: does the reality of lift ticket pricing in Europe mean that all facets of a ski vacation will be cheaper than in the U.S.? Well, no. The biggest complicating factor might be lodging. In major Alpine destinations like Zermatt, St. Anton, Verbier, Courchevel, or St. Moritz, accommodation can be just as expensive—if not more expensive—than staying in Aspen, Vail, or Jackson Hole. Off-site vacation home rentals do exist at much better values, but if you don’t have a rental car, they may be tough to reach.

Depending on which European ski town you stay in, food can be rather expensive as well. In the highest-end towns, it’s not out of the ordinary to see €25–€40 for a basic meal and much more for table-service. It is worth noting that if you know what you’re doing, grocery stores can often be an easy workaround to this cost, with most European ski towns having full supermarkets with affordable and reasonably-high-quality ready-to-eat meals. Still, once lodging, dining, and Trans-Atlantic plane travel are factored in, the total cost can still rival or exceed a U.S. ski trip.

Lodging in European ski towns can be priced variably, but the most convenient and walkable accommodations in the highest-end villages are often extremely expensive.

Final Thoughts

So yes, Europe has the edge in infrastructure investment and public funding mechanisms, and the average skier or rider can still wake up, decide to hit the slopes at the last minute, and pay less than €100 to ride more terrain than most Americans will ever see in a lifetime. Let’s be clear: many American ski resorts can still be accessed for reasonable rates if you make your purchase well in advance, and if you plan to ski for over a week using a multi-resort pass product, the value propositions start to equal out. This all being said, for the average person, Europe just offers way more for a much lower ticket price.