Why Telluride’s Ski Patrol Strike Ended Badly for Everyone

On December 27, 2025, visitors to Colorado’s Telluride ski resort arrived to a milestone day in the resort’s history. That day marked the start of the first full resort shut down due to a ski patrol labor strike in North American history, with the resort’s ski patrol union voting to authorize that disruption due to unresolved wage discrepancies. But what originally started as a valiant fight for fair wages quickly turned into something much more complicated.

So what exactly has been going on with Telluride over nearly the past two weeks? What exactly has ski patrol been asking for, and how are patrollers at Telluride charged with such a complex job compared to a typical mountain? Why has management held out on giving the patrollers what they want? And just how devastating is the economic impact from the strike to the town itself? Well, we had the opportunity to go to Telluride ourselves and check out this situation on the ground.

How Did We Get Here?

First, we have to start with some background about how we got to this stalemate in the first place.

The previous contract for Telluride’s ski patrol expired on August 31, 2025. Negotiations between the patrollers and resort management were ongoing, but by the time the season started, no agreement had been reached.

The ski patrol union’s main demands were an increase in starting wage to $28 per hour, and an increase in wages for the highest-earning senior patrollers to somewhere between $40-48 per hour. In response, Telluride management offered an increase in starting wage to $24 per hour, up from the previous $21, and their proposed raises for the senior patrollers topped out at under $40 per hour. The resort’s leadership argued this was a sustainable compromise, but the union maintained that these numbers were insufficient.

Initially as this ski season began, the patrollers worked without a contract. But with a lack of progress in negotiations, the union authorized a strike starting December 27. The resort then announced that they would fully suspend operations for the strike’s duration, an unprecedented decision. Notably, Telluride owner Chuck Horning is an independently wealthy individual who has majority control over the resort, and thus theoretically answers to no one for decisions like this.

With no resolution in sight after nearly two weeks, we decided to fly to Telluride to check out this extraordinary situation for ourselves.

Telluride’s ski patrol has pointed to the highly specialized demands of managing terrain like Palmyra Peak, which can require more than two hours of hiking just to reach, as justification for higher wages for senior patrollers.

Sunday, January 4

I arrived in Telluride on January 4 to what was essentially a ghost town for that time of year. Because of a 2 1/2 hour flight delay, I missed the ski patrol picket lines for the day. So instead, I decided to go straight to some of the local businesses to get the scoop on what was going on.

Everyone knows each other really well in this town, and very few people were even willing to speak with me on the record. That evening, the few people who were willing to let me speak with them on the record asked that we not include their faces. And what these locals had to say described a town that should have been full, but simply wasn’t.

After visiting a couple of businesses in the town of Telluride itself, I decided to take the free gondola, which had been the only lift running because it’s technically a piece of public transportation infrastructure, over to the Mountain Village side of the resort. If you’ve never been to Telluride, you can think of the town of Telluride as the old town historical development, and the town of Mountain Village as the ritzy new condo development, kind of like equating Aspen to Snowmass, except if there were a gondola connecting the two and they were a lot closer to each other. I spoke with a gondola employee off the record right before loading the lift and learned that many employees were already beginning to quit and leave town, which meant that Telluride would face staffing shortage issues upon reopening.

While the resort itself was shut down, the Mountain Village gondola continued to operate in its role as local public transportation.

Upon arriving at Mountain Village, it was clear that this side was even emptier than town. But I did have the chance to go to a few shops and talk to some local townspeople and employees. While everyone we spoke to in Mountain Village asked to remain off the record, here is a little summary of what I learned:

As in town, we heard that the shutdown was translating into real economic pain, with several workers describing the same lack of visitation on this side of the gondola. We also heard longer-standing frustrations around stagnant infrastructure, lackluster on-mountain dining, and underinvested snowmaking as sources of economic tension that predate the strike. But most notably, I spoke with several lift operators, including first-year employees. Those newer workers expressed uncertainty about what would happen if the shutdown dragged on past January 11, noting that they were still being paid until then but had no clarity beyond that. While some felt personally insulated due to savings or backup plans, others acknowledged that many workers are living paycheck to paycheck and could be forced to leave town if hours are cut or layoffs began.

Then, I returned to the town side, and was able to speak on the record with a restaurant worker who’s lived in Telluride nearly his entire life.

I also spoke with a couple more people before the end of the night, including a bartender and a local real estate agent, but they requested to remain off the record. Nevertheless, what seemed to be a chief concern for most was the negative economic impacts toward the town’s businesses and the workers who operate them.

The town of Telluride itself was suffering pointed economic setbacks as a result of the resort shutdown.

Monday, January 5

The next morning, January 5, it actually began to snow in town and around the resort. And in an interesting development, Telluride officially opened the Lift 1 Chondola with extremely limited terrain, meaning that ski operations were back on, albeit in a very reduced capacity. We also learned that Lift 1 had been unofficially spinning the prior afternoon as well.

I began the day by checking out a well-known bakery in town, which typically has lines out the door, but only had a few people in front of me today. I got the chance to speak to a worker there and ask about her experience throughout this whole situation.

She then provided an example of just how desperate some people in town were getting for work.

However, not every business in town had been affected negatively up to this point. And this was illustrated by the next person I spoke with.

The main concern for many seasonal workers was the idea of losing hours or even being laid off due to the lack of tourism.

So we’d heard a lot from the townsfolk, but of course, my main goal for the day was to speak to the ski patrollers. However, first I had to find them. Once again, the strikers were nowhere to be seen in town, despite several locals telling me that they were usually picketing near the town gondola loading zone starting around 10am. So it was time to once again head to the Mountain Village side, which also happened to be where the very limited terrain at the resort was now open.

While waiting at the ticket window, I spoke with another local and her friends who were here for vacation.

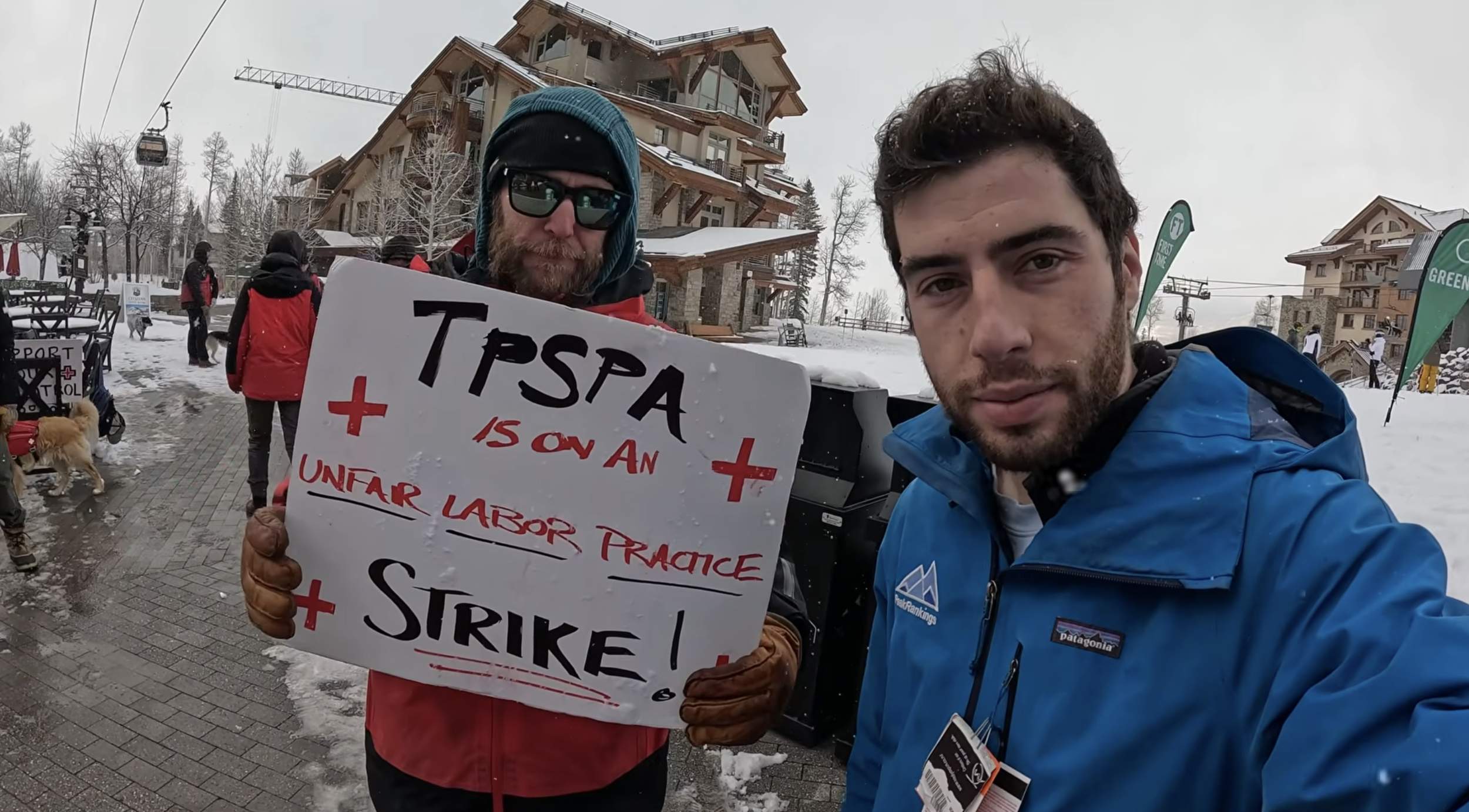

But finally, after leaving the pass building and heading up to Lift 1, I found the striking ski patrollers I’d been searching for so long to talk to.

As we alluded to earlier, being a patroller at Telluride is not a typical ski patrol job. While I was on site, I wanted to understand firsthand what the work here actually entails, particularly on the resort’s most extreme terrain.

After searching for them for nearly a full day, I finally had the chance to talk directly with the ski patrol union.

After hearing the patrollers’ side of the story, I went for a few laps on the mountain’s only open lift to see if I could speak to any guests.

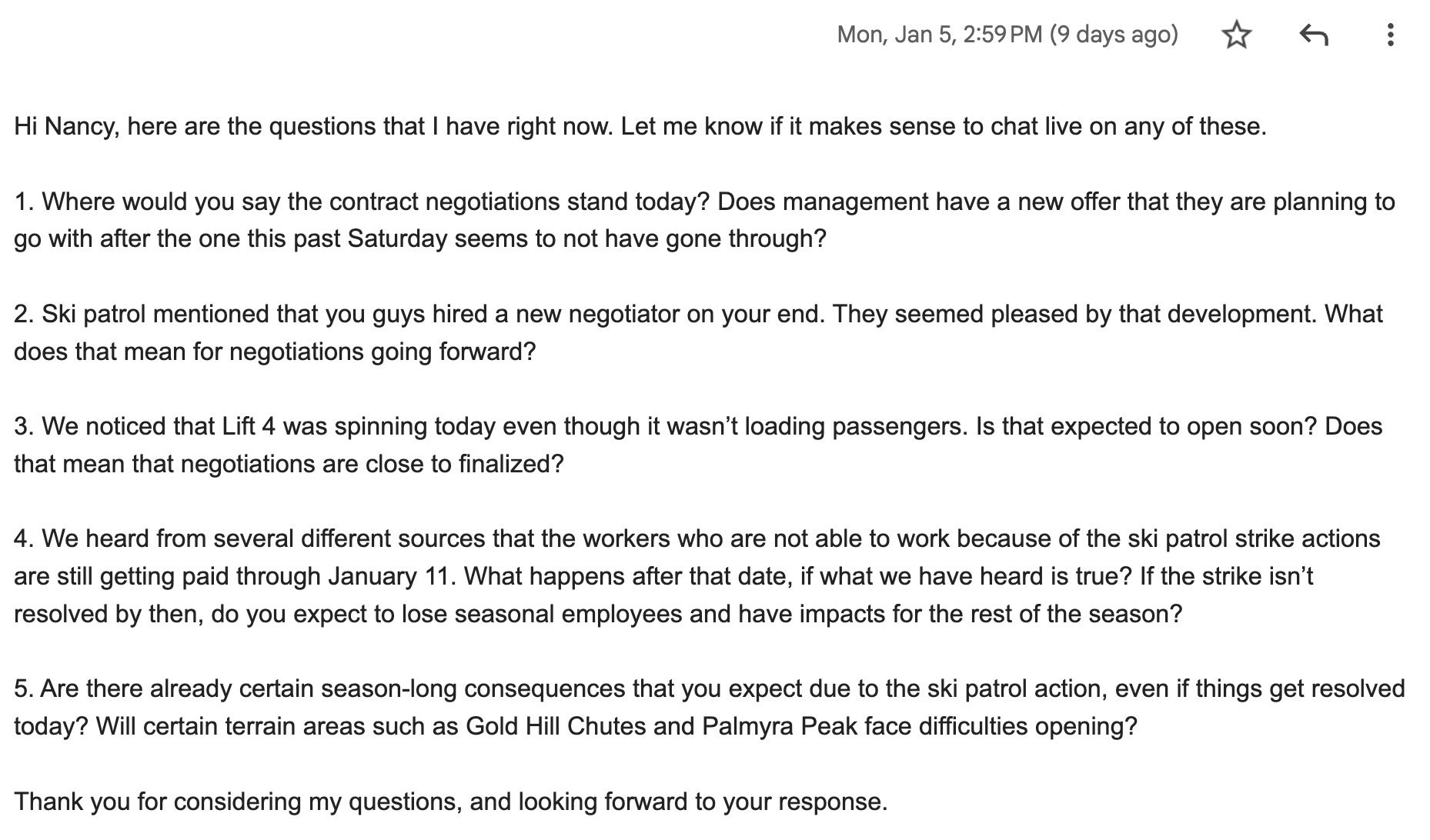

After talking with pretty much every other party that was affected by the strike, the final group we hadn’t heard from was Telluride’s management itself. Unfortunately, I learned while on the slopes that talking to someone live was going to be very difficult, as the PR director for Telluride was the only person who was authorized to give a statement and she was out of office. One of the mountain information folks was nice enough to give me her contact details, and I asked to organize a chat with her to get her statement on the situation. She asked if I could email her the questions I had. Those questions and her response are pictured below.

My questions to Telluride’s management.

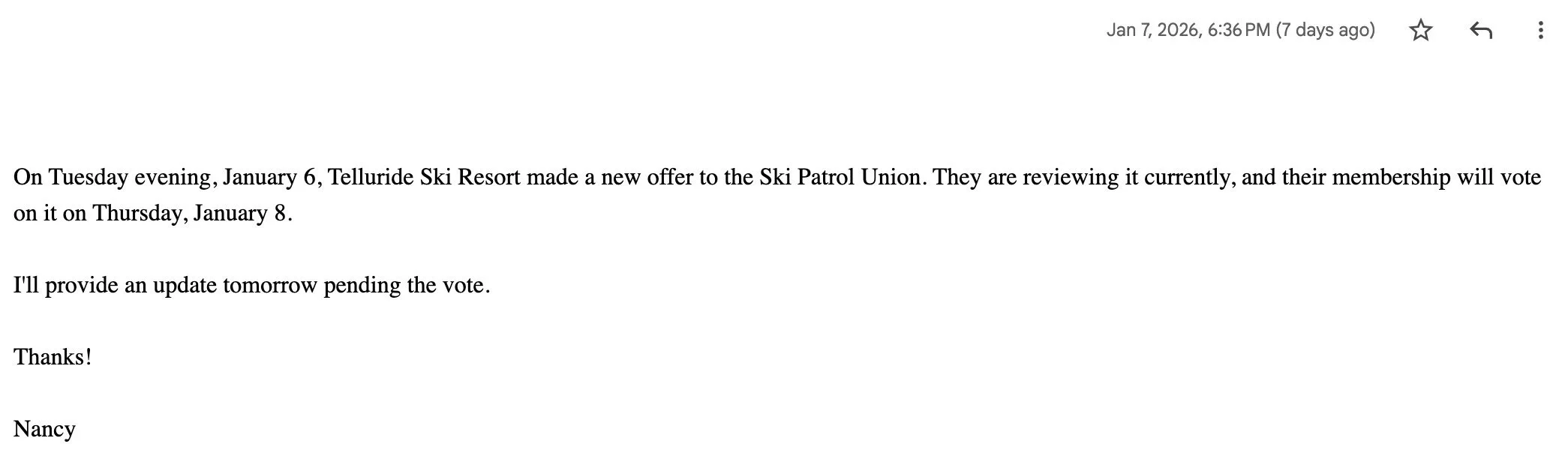

The response from Telluride’s PR director.

A Tense Atmosphere

It was clear that many people in town supported the union’s cause on paper. However, it was also clear that the overall attitude toward the patrollers was becoming increasingly mixed. Several people we spoke with, inhabiting a diversity of jobs and roles within the Telluride ecosystem, expressed growing frustrations at how the strike was affecting the rest of the town.

“At what point are you going to sacrifice the entire town? Because now everybody’s feeling it.”

However, it wasn’t as cut-and-dry as simply blaming the patrollers. In fact, that was far from the case. Nearly everyone who expressed anger at the strike also pointed to resort management and owner Chuck Horning as bearing significant responsibility for how the situation reached this point.

After what may have been my shortest day on a ski slope at a major resort ever, I left town with a clear sense that things were more complicated than they had appeared through the media, and that morale across all affected parties was low. Townspeople still supported the patrollers in principle, but the devastating economic effects of the mountain being closed were taking their toll, and with the desperation that came from that, it became clear they felt they had to start putting their own interests first. We especially got a sense of that from one of our conversations.

Just two days after I left, things in town reached a boiling point. Members of the town community took to the streets to protest the economic devastation and call for the patrollers to reach an agreement with the resort as quickly as possible. This was followed by a heated town meeting later that night, where many of the same concerns were highlighted.

It also recently emerged that Mountain Village’s mayor and Telluride’s mayor pro tempore flew to California to meet with resort owner Chuck Horning shortly after the strike began to explore a majority buyout of the resort. The plan was not successful. Notably, the Mountain Village mayor has a background as a ski patroller, but was not part of the union or strike action. The meeting was not disclosed in advance to the town council, quickly became controversial, and triggered an internal investigation. The Mountain Village mayor resigned days later.

The bunny hill served by the Lift 1 Chondola was the only open terrain during our visit.

Did Anyone Win in the Telluride Ski Patrol Strike?

Ultimately, on Thursday afternoon, the patrollers reached an agreement with Telluride management. This ended the strike and resulted in the patrollers returning to work on Friday, January 9. Ironically, this meant that the Telluride strike started and ended on the exact same calendar dates as the Park City strike one year prior.

However, unlike the resolution at Park City the year before, the overall tone and several key aspects of the outcome suggested that Telluride’s patrollers were far from victorious. To start, neither the resort nor the patrol was willing to disclose the wage and compensation terms of the new agreement. On its own, that kind of opacity could simply indicate that one side was embarrassed by the result, without clearly signaling which side that was. But it quickly became apparent that the decision to end the strike was not unanimous among the patrollers, and that several remained concerned about the cost-of-living implications of the deal they accepted. Taken together, these details point to a resolution driven more by the need to end the shutdown than by the successful achievement of the patrollers’ core demands, with significant wage and affordability concerns left unresolved.

So if the signs are pointing to where we think they are, why exactly did Telluride’s ski patrol strike fail to achieve its fundamental goals? In our view, it’s not because patrol was wrong in pushing for higher wages; rather, it’s because their leverage just wasn’t there. And there are several structural reasons for that.

Why Telluride’s Ski Patrol Union Likely Failed to Achieve Its Goals

The pain landed on town, not ownership.

Because Telluride’s management chose to shut down the ski resort entirely, the immediate economic damage was absorbed by service workers and small businesses. That dynamic quickly turned community pressure inward rather than upward.Ownership is insulated from short-term losses.

As a privately held resort owned by an ultra-wealthy individual, Telluride is structurally resistant to short-term financial pressure. The classic “bleed them until they move” strike logic doesn’t function the same way in this context.The local economy is single-industry and highly fragile.

In Telluride, nearly every job depends on the mountain. That means a patrol strike doesn’t just pressure management, it destabilizes the entire town. Social solidarity erodes quickly under those conditions.Local political leadership fractured under pressure.

The revelation that the Mountain Village mayor and Telluride’s mayor pro tempore privately flew to California to explore a buyout without informing the town council signaled declining confidence among top local political leaders in the negotiations, reflected in actions taken outside public view and only revealed later, and a turn toward searching for off-ramps rather than reinforcing labor’s leverage.Low snow reduced guest-side pressure.

A thin snow year dampened outrage from visitors and reduced external amplification. The strike unfolded in a season when many guests were already ambivalent.Management had already moved partway on compensation.

Whether patrol finds it adequate or not, the existence of a substantial raise offer weakens the public narrative of emergency underpayment and complicates broader solidarity.

Why The Outcome May Be Troubling for Telluride’s Long-Term Health

The implications of all this may be more serious than a single failed strike. If the people responsible for opening and safeguarding some of the most extreme in-bounds terrain in North America feel structurally undervalued, the long-term risk is not necessarily another walkout, it’s quiet attrition. At a place like Telluride, where terrain such as Palmyra Peak requires significant staffing just to open and manage safely, losing experienced patrollers could mean that some of the mountain’s most iconic lines simply stop opening with any regularity. That’s a terrible long-term trajectory for a resort that has become such an iconic destination in large part because of these extraordinary in-bounds lines.

The poor snow conditions across Colorado in general may have contributed to a lack of care amongst guests about whether or not Telluride was fully open.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, it is difficult to argue that anyone emerged from the Telluride ski patrol strike unscathed. The patrollers did not appear to secure their core demands. Resort management further strained already fragile relationships with the community, and those strains become much more visible to the broader public outside of town. And the townspeople, many of whom initially supported patrol, were ultimately caught in the crossfire of the negotiations and absorbed serious economic damage as the shutdown dragged on.

It seems like the strike did end in time to avoid a true season-long economic catastrophe, but when the dust settled, the resort itself appeared to have come out ahead more than any other party. It did so, at least in effect, by allowing pressure to fall on two groups of working-class people and letting those tensions turn inward. That dynamic is neither new nor accidental. It is a familiar pattern in labor disputes where ownership is insulated and communities are not.

For the Telluride community, the situation remains deeply complicated. If you already have a trip planned, canceling it may feel principled, but that risks doing more harm to the local workers and families who had no control over the dispute and bore much of the cost than the resort itself. With the strike now over, terrain openings are beginning to return to more normal levels, at least for this season. However, what remains unclear is the longer-term impact after 2026, particularly whether Telluride will be able to retain the experienced patrollers needed to safely open and manage its most demanding terrain.