A Major Epic and Ikon Pass Fraud Scandal Has Been Exposed. What Does It Mean?

Background

In late 2020, skiers in Utah began encountering tantalizing offers online: “Discounted Ikon and Epic Passes”—season passes for world-class ski resorts at prices well below face value. Behind these offers was 29-year-old Jamilla Greene from Fort Mill, South Carolina, who, along with other associates, launched these ads marketing two of the ski industry’s most coveted products: Vail Resorts’ Epic Pass and Alterra’s Ikon Pass. These passes normally grant access to multiple world-class resorts and can cost between $600 and $1,500 USD each, so a cut-rate deal was sure to attract budget-conscious snow enthusiasts. The team capitalized on this by posting ads in ski community forums and online classifieds (from KSL Classifieds to Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace) wherever skiers and riders might look for deals. The pitch was simple: season passes or lift tickets at a “discount”, no catch—except, of course, there was a very big catch.

A mockup example of what an email exchange could have looked like between the fraudsters and a potential buyer

What buyers didn’t know was that Greene had no authorization from resorts to sell discounted passes, and they weren’t absorbing the cost difference out of generosity. Instead, the scheme’s origin lay in a mix of identity theft and clever social engineering. When an interested skier or rider responded to one of the ads, Greene or her co-conspirators would move the conversation to private channels—be it text messages, emails, social media DMs—to build trust and gather the personal details needed to buy a pass (name, age, address, etc.). From the outside, it appeared as if Greene was facilitating a routine purchase on the customer’s behalf. In reality, she was preparing to use stolen credit card information to foot the bill.

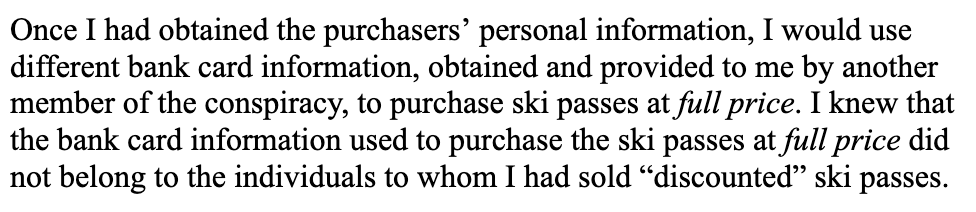

Armed with the buyer’s personal details, Greene would log onto the official online ticket portals for the relevant resort or pass (Ikon’s or Epic’s website, or a specific resort’s system) and purchase the pass at full price using someone else’s stolen credit card information obtained through illicit means. To the legitimate cardholders and banks, these charges looked like any other expensive ski pass purchase, and it could be weeks before they noticed and reported fraudulent activity. Meanwhile, the buyer would send payment for this “discounted” pass directly to Greene through peer-to-peer apps like Venmo, PayPal, Zelle, or Apple Pay. Notably, PayPal and Apple Pay were used in peer-to-peer mode, not merchant mode, meaning they didn’t accept credit cards and there was no chargeback protection. Greene then delivered the newly bought digital pass or lift ticket to her customer, often via email or even physical mail in some cases. In essence, Greene created a middleman transaction: using a stolen credit card to give a customer a legitimate pass, then pocketing the buyer’s money for herself. It seemed like a win-win for her—until, as recent court filings note, the scheme began to snowball out of control.

The Scheme Grows

What started quietly in late 2020 grew over the next four ski seasons into what prosecutors describe as a “multi-year, multimillion-dollar scheme.” By 2021 and 2022, more buyers began responding to online listings and referrals circulating within ski communities. Who doesn’t like a good bargain after all—and if you get one, are you just not going to share with your friends? Greene and her team placed targeted ads in ski towns not just in Utah but “elsewhere” as well, meaning the scam’s reach extended beyond a single state. Since the fraud persisted across multiple seasons, it was clear that the team’s demand for discounted passes remained steady or increased year after year.

As the client list expanded, so did the need for more stolen credit card numbers and more collaborators to handle the volume of transactions. According to federal investigators, Greene’s co-conspirators shared these stolen card numbers amongst themselves, using them interchangeably to make the fraudulent purchases. At no point were the skiers and riders buying these passes aware of the fraud behind the scenes; from their perspective, they paid Greene or an associate, and they received a valid pass that showed up officially on the Epic or Ikon website, in their name. For a while, these scammed customers didn’t actually notice anything wrong with their passes, and in some cases, they were even able to use them.

Many victims of the scheme were able to use the fraudulent passes to get through RFID gates and board lifts at resorts, such as the Collins lift at Alta pictured above.

By early 2023, the scam was running at full tilt. It now involved “various Utah mountain resorts” beyond just the big multi-resort passes. In addition to Ikon and Epic passes that unlocked dozens of resorts (including Utah’s Alta, Snowbird, Deer Valley, Solitude, Brighton, Snowbasin and Park City), the crew also offered “discounted” single-mountain season passes and even day lift tickets for individual resorts. The financial scale of the operation climbed into the millions. Investigators would later conclude that the conspiracy resulted in “millions of dollars of loss” borne by resorts and financial institutions once the dust settled. Extrapolated across multiple resorts and several seasons, it’s clear the scheme facilitated thousands of bogus transactions.

Throughout this expansion, the methods remained straightforward and surprisingly low-tech. The fraudsters didn’t hack any resort systems or forge pass IDs; they simply exploited the e-commerce convenience that resorts offered. By using real personal details of the buyer with a stolen card, the purchases passed security checks; the names matched the pass users, and the charges initially went through since the card details were valid (even if they weren’t legally theirs to use). After all, people buy passes for others all the time, whether it be as a gift, for others in their ski group, or acting in a travel agent capacity. The perpetrators likely assumed that any single fraudulent chargeback here or there would be written off as a one-time incident (and more on what those chargebacks meant for the scammed customers in a minute). For a while, they were right—but it was only a matter of time until unusual patterns gave them away.

The fraud scheme was uncovered when the large amount of credit card chargebacks grew too large to remain unnoticed.

Note: example image for illustrative purposes only

How the Fraud was Exposed

The scheme did not unravel because of a single catastrophic mistake. Instead, it began to surface the way many large financial frauds do: through accounting anomalies that no longer fit within the range of normal error.

During the 2022-2023 ski season, multiple Utah resorts began seeing elevated levels of credit card chargebacks tied to lift tickets and season passes. Chargebacks are not unusual in the ski industry; lost cards, family disputes, or travel cancellations all generate occasional reversals. However, the volume and consistency of these reversals began to raise internal suspicions. According to later federal summaries and independent ski-industry reporting, Big Cottonwood Canyon’s Brighton ski resort emerged as one of the first mountains where the irregular pattern became impossible to ignore.

By early 2023, Brighton had identified a concentrated cluster of disputed transactions associated with lift access products that had already been issued and, in many cases, used. From the resort’s perspective, this meant something more serious than buyer’s remorse: banks were clawing back funds weeks after the fact because the underlying credit cards had been reported stolen. Over a relatively short period, the total value of these reversals climbed into the tens of thousands of dollars—well beyond what would be expected from routine disputes. While exact figures were not disclosed by prosecutors, independent reporting found that Brighton identified over $50,000 in fraudulent pass purchases in just a four-month window.

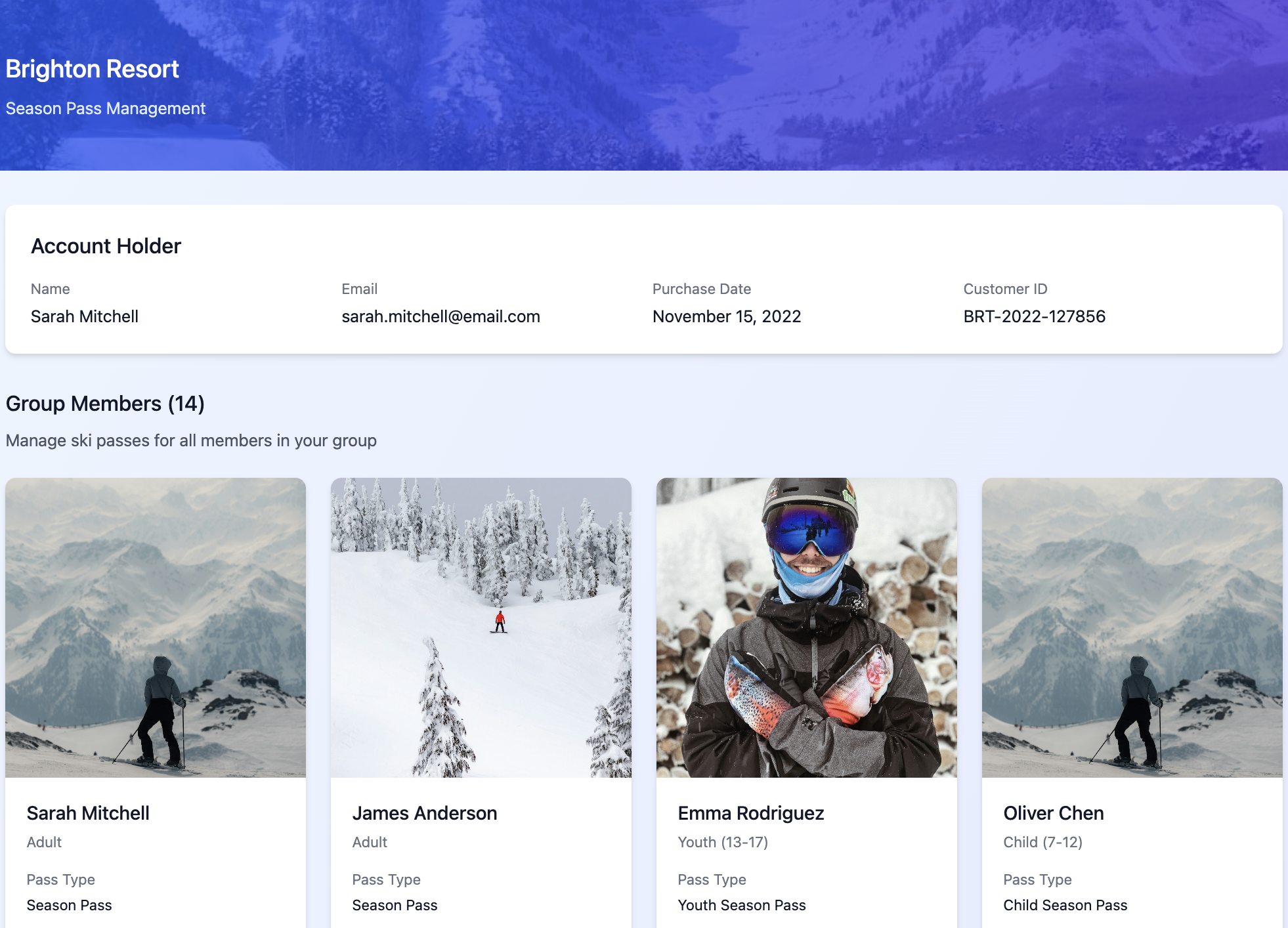

As Brighton’s ticketing and finance teams reviewed the affected transactions, another anomaly stood out. A disproportionate number of the disputed purchases traced back to the same customer account within the resort’s online sales system. That account appeared to be purchasing lift access for numerous individuals, behavior that strongly diverged from normal guest usage patterns. Rather than a single visitor or family buying passes for themselves, the account functioned more like a distribution hub.

Brighton was the first resort to notice anything wrong with tickets and passes being used on its slopes.

Note: example image used for illustrative purposes only

Further review revealed that at least some of the passes linked to that account were actively being used on the mountain. Resort staff flagged the situation internally and escalated it to law enforcement, suspecting the activity was part of a broader fraud operation rather than isolated misuse. At that point, the issue moved beyond resort loss prevention and into criminal investigation territory.

When authorities began speaking with skiers and riders whose access had been tied to the flagged transactions, a clearer picture emerged. These individuals reported that they had purchased what they believed were legitimate, discounted multi-resort passes through informal channels, often via personal referrals or online listings rather than official resort platforms. In several cases, the passes initially worked without issue, reinforcing the perception that the transactions were legitimate.

However, that illusion collapsed once the underlying credit card fraud was discovered. After cardholders disputed the unauthorized charges, resorts and pass operators voided the associated passes. Buyers found their access abruptly revoked, sometimes mid-season, after receiving notices that the payment method used for their pass had been invalidated. As a result, they were left with no pass at all and hundreds, if not thousands, in squandered value.

By the time law enforcement formally intervened, Brighton’s findings had become a critical entry point into a much larger investigation. Resort transaction data, combined with payment records from peer-to-peer apps and online communications with buyers, allowed investigators to trace the activity outward. What may have initially appeared to be a localized anomaly was soon connected to similar fraudulent purchases across multiple resorts, most notably those in Utah and Colorado, as well as national pass platforms, all following the same basic structure: stolen credit cards upstream, discounted resale downstream, and digital peer-to-peer payment apps with no fraud protections acting as the bridge.

Federal agencies, including the U.S. Postal Inspection Service because of the physically mailed passes, became involved as the investigation expanded. And by mid-2025, authorities had assembled a comprehensive view of the operation’s scope, revealing a coordinated, multi-year fraud network rather than a one-off resale scam. Crucially, by tracing the money flows on the peer-to-peer payment apps and the communication logs with buyers, law enforcement honed in on Jamilla Greene and others in her circle, culminating in her arrest in late 2025.

The top of the Crest 6 chairlift at Brighton

Impact on Resorts and Skiers

When the scheme finally unraveled, it became clear that a lot of people got burned. Federal investigators noted that each fraudulent transaction in this scam effectively created up to “four separate intended victims.” Let’s break that down:

1. The Credit Card Holder: This is the person whose card information was stolen. They were victimized by having fraudulent charges run up, often totaling hundreds or thousands of dollars, for ski passes they never personally bought. These individuals had to go through the hassle of reporting fraud, canceling cards, and disputing charges, often noticing them weeks or even months after they first posted. Also, they had to deal with the anxiety of knowing their financial info was misused.

2. The Credit Card Company or Bank: When fraudulent charges are reported, banks typically foot the bill via refunds and write off the losses. In this case, banks had to deal with multiple large chargebacks for ski passes, collectively amounting to huge losses that likely fell into the tens of thousands of dollars range. In the grand scheme of fraud rings, this probably ended up being a rounding error for gigantic financial institutions like Chase or American Express, but the impact could have still been large enough that to cost an entry-level analyst’s first-year salary.

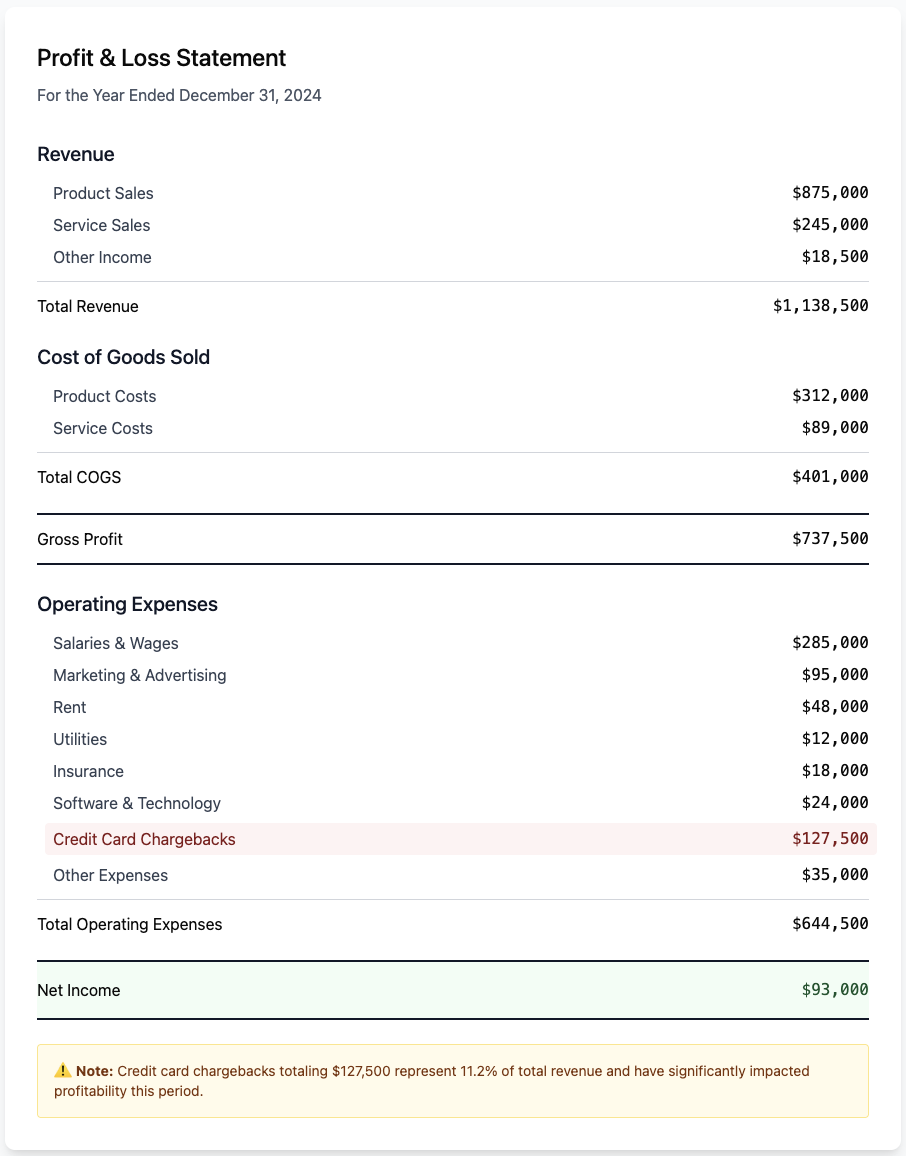

3. The Ski Resorts: The resorts and pass companies like Vail Resorts (Epic) and Alterra (Ikon) were left holding the bag for services already rendered. A disputed charge meant the resort had already issued a valid pass or ticket and perhaps provided days or weeks of mountain access, only to have the revenue from that sale clawed back. Across various impacted resorts, these chargebacks stacked up to large-scale losses. Beyond the direct financial hit, resorts had to devote employee time to investigating irregularities, and while we can’t know for sure, we wouldn’t be surprised to see them invest resources in tightening their e-commerce fraud detection after being exploited by this scam. Some of you might be wondering if this fraud loss shows up on Vail Resorts’ public financial statements, but because the amount likely wasn’t large enough to be material to investors—and the company’s P&L statements present revenue net of refunds and reversals—it’s impossible to tell just how much the company was affected by this scheme.

4. The Pass Buyer: Ironically, the skiers and riders who paid for the “discounted” passes became victims in the end. Many of them thought they were simply snagging a great deal from a third-party seller and likely enjoyed a brief period using their passes. But as we saw, once the stolen card’s owner noticed the fraud, the resorts canceled the tickets/passes without warning. Skiers and riders arrived at lifts only to find their pass invalid or received belated emails that their season pass was revoked due to a payment dispute. They lost the money they paid to the scammers—which, because they didn’t pay via a method with chargeback protections, was never able to be refunded. Those customers at Brighton, for example, paid for Ikon passes that were voided a month later—and they just had to eat the losses without being able to ski or ride for the rest of the season.

The scheme had far-reaching consequences for those using Epic and Ikon passes to take trips abroad to places like Europe, Japan, New Zealand, or South America.

In total, thousands of skiers and riders were likely affected over the course of the four-year scam, though an exact headcount hasn’t been released by prosecutors. We do know the fraud encompassed “multi-millions” of dollars in passes. If, hypothetically, even just $2 million of products were fraudulently sold at an average of $800 each, that’d be 2,500 passes or tickets, giving a rough sense of scale for the number of buyer victims. The number of distinct stolen credit cards used could be quite large as well; given the risk, they likely burned through hundreds of card numbers if the scam was able to last as long as it did. Epic and Ikon undoubtedly saw multiple fraudulent purchases, and it’s documented that resorts like Alta and Breckenridge did as well. Each resort had to systematically identify and cancel fraudulent passes once alerted. The fallout reached beyond Utah and Colorado as well; since Epic and Ikon passes grant access at resorts worldwide, a canceled pass in Utah would no longer work at other mountains either, stranding some travelers who might have bought a “discount” pass for a big ski trip. And from the text of the legal documents, it’s clear that buyers from at least three states—Utah, Colorado, and New York, and credit card holders from at least nine states—Utah, Arkansas, Wisconsin, Texas, Alabama, Georgia, Oregon, Washington State, and North Carolina—were victims here.

If the number of victims is anything to go by, it’s clear to see the human impact was significant.

Excerpt from Jamilla Greene’s guilty plea

The Crackdown: Federal Charges and Co-Conspirators

Once the investigation traced back to Jamilla Greene and her collaborators, it seems that federal prosecutors moved quickly. In December 2025, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Utah formally charged Greene with conspiracy to commit wire fraud, a felony. Rather than face a grand jury indictment, Greene was charged via a felony information on December 1, 2025, a sign that she waived indictment to speed up a guilty plea. Indeed, on December 9, 2025, Jamilla Greene pleaded guilty in federal court to the wire fraud conspiracy, admitting her role in orchestrating the multi-year ski pass scam. This charge carries a maximum penalty of up to 20 years in prison, not to mention hefty fines and restitution orders for the damages caused. By pleading guilty, Greene likely hopes for some leniency at sentencing, but she will still face serious time behind bars given the scope of the fraud.

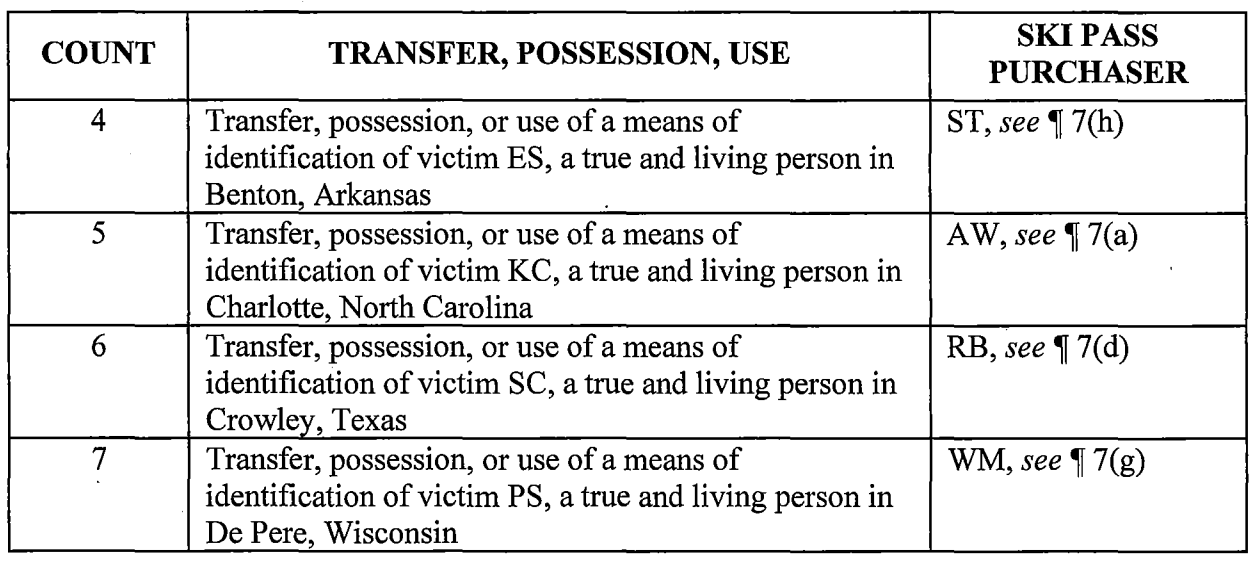

Greene wasn’t acting alone, and we’ve now learned who one of her alleged associates was. The day after Greene’s plea, on December 10, 2025, a federal grand jury indicted 41-year-old Jonathan Rembert on a slate of charges for his alleged part in the operation. Rembert is accused of being one of the key players who communicated with buyers, gathered stolen card info, and received payments in the scam’s financial network. The indictment hits him with conspiracy to commit wire fraud (the same overarching charge as Greene) and conspiracy to commit mail fraud, adding that elevated charge because some passes were physically mailed and the postal system was used to further the scheme. Additionally, Rembert faces charges of aggravated identity theft and possessing 15 or more unauthorized access devices (which, in plain terms, means holding a cache of stolen credit card numbers; also it’s the literal name of the charge, meaning it’s the same federal crime regardless of whether you have 16 or 3,000). The identity theft charge is particularly serious; it carries a mandatory two-year prison term on top of any other sentence if convicted, due to the nature of using someone’s personal data in a fraud scheme.

Rembert’s initial court appearance in Utah was scheduled for January 7, 2026. Being indicted suggests he has not (at least yet) taken a plea deal, so his case is on track to proceed to trial unless he opts to plead guilty later. Prosecutors allege that Rembert directly profited from the scam; the money from buyers often went “directly into the accounts of Rembert and his coconspirators” and was divvied up for personal use. In other words, Rembert is painted as a central figure in handling the dirty money. It’s worth noting that Rembert, unlike Greene who has already entered a plea, is presumed innocent until proven guilty in court. However, the indictment suggests the evidence against him is substantial, likely including paper trails of bank transfers and communications linking him to the fraud, and perhaps suggests he played even more of a leading role than Greene did.

Investigators haven’t publicly named other co-conspirators yet, but all indications are that more people were involved in the peripheries. Given the scale of the scheme, it’s possible there were others in charge of sourcing stolen credit card data, additional people placing ads or referring clients, or helpers who managed the multiple resort accounts. The U.S. Attorney’s Office has emphasized that the investigation is ongoing, even after these two main players were charged. This means we may see more indictments or charges as agents sift through records and perhaps flip cooperative witnesses. It wouldn’t be surprising if one or several additional people in Greene and Rembert’s circle face legal consequences before this is over.

Some of the identity theft charges leveraged on Jonathan Rembert

Source: United States of America v. Jonathan Rembert - INDICTMENT

Aftermath and What Comes Next

With Jamilla Greene’s guilty plea secured and her sentencing on the horizon, the focus turns to the broader scope of the operation. Greene is scheduled to be sentenced on February 24, 2026 in a Salt Lake City federal courtroom. Meanwhile, Jonathan Rembert’s case is making its way through the legal system starting this month.

But at least to the public eye, it seems like there are still a ton of unanswered questions. How did Greene, Rembert, and their associates obtain so many stolen credit card numbers? Was there an organized identity theft ring feeding them info? Did they purchase dumps of card data online? The indictment and press releases don’t detail this, but law enforcement may pursue those avenues, potentially leading to cases beyond the ski pass angle (for instance, charging those who supplied the stolen data).

From an industry perspective, the story of the ski pass scam is both fascinating and a big lesson. While the warning signs of buying a third-party pass like this would probably be obvious to the average person watching this channel, it revealed a blind spot in how high-value ski products are distributed—and, to a certain extent, could be argued to play off peoples’ allure to save any money off the exorbitantly rising cost of mountain access these days. Just take for example the person who bought the Breckenridge ski pass. Even if he wanted an in-advance ticket for one single day, he likely would have been facing daily rates of over $200 through official channels based on the time of year he bought. And even outside of the rising costs themselves, for years, skiers and riders have swapped lift tickets or sold off extra days on multi-passes informally, and a small gray market for discounted tickets has existed. But this is the first time anything on this scale has been laid bare.

As of this writing, the snow sports world still has a lot of waiting to do for this case to fully close. But one thing is clear: in life, as on the slopes, shortcuts often lead to perilous terrain.